PART V : PROVIDENCE, JUSTICE AND MERCY¶

25. Providence And Divine Justice¶

Now that we have spoken of providence in itself and its attitude to souls, we may suitably consider it in its relations with divine justice and with divine mercy. As in us prudence is connected with justice and the rest of the moral virtues, which it directs, so also in God providence is united with justice and mercy, these being the two great virtues of the love of God in our regard. Mercy has its foundation in the sovereign good in so far as it is of itself diffusive and tends to communicate itself externally. Justice, on the other hand, is founded in the indefeasible right of the sovereign good to be loved above all things.

These two virtues, says the psalmist, are found combined in all the works of God: “All the ways of the Lord are mercy and truth” (Ps. 24: 10). But, as St. Thomas remarks, Cf. St. Thomas, 137 in certain of the divine works, as when God inflicts chastisement, justice stands out the more prominently, whereas in others, in the justification or conversion of sinners, for example, it is mercy that is more apparent.

This justice, which we attribute analogically to God, is not that commutative justice which regulates mutual dealings between equals: we cannot offer anything to God that does not belong to Him already. It is a distributive justice, analogous to that which a father shows toward his children or a good monarch toward his subjects. Thus, by reason of this justice of His, God first of all sees to it that every creature receives whatever is necessary for the attainment of its end. Secondly, He rewards merit and metes out punishment to sin and vice, especially if the sinner does not ask for mercy.

We shall do well to consider how providence directs the action of justice (1) during the course of our earthly existence, (2) at the moment of death, and (3) after death.

Providence and justice in the course of our earthly existence

Providence and justice combine in this present life to give us whatever is necessary to reach our true destiny: that is, to enable us to live an upright life, to know God in a supernatural way, to love and to serve Him, and so obtain eternal life.

There is a great inequality, no doubt, in circumstances, natural and supernatural, among men here on earth. Some are rich, others are poor; some are possessed of great natural gifts, whereas others are of a thankless disposition, weak in health, of a melancholy temperament. But God never commands the impossible; no one is tempted beyond his strength reinforced by the grace offered him. The savage of Central Africa or Central America has received far less than we have; but if he does what he can to follow the dictates of conscience, Providence will lead him on from grace to grace and eventually to a happy death; for him eternal life is possible of attainment. Jesus died for all men, and among those who have the use of reason only those are deprived of the grace necessary for salvation who by their resistance reject it. Since He never commands the impossible, God offers to all the means necessary for salvation.

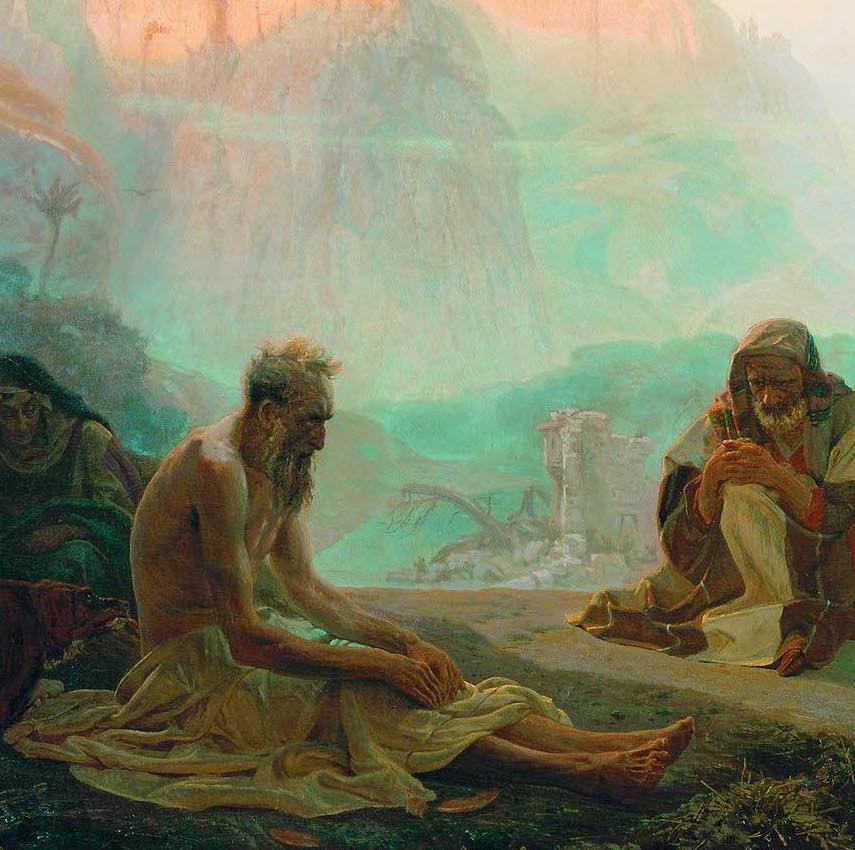

Moreover, not infrequently providence and justice will make up for the inequality in natural conditions by their distribution of supernatural gifts. Often the poor man in his simplicity will be more pleasing to God than the rich man, and will receive greater graces. Let us recall the parable of the wicked rich man recorded in St. Luke (16: 19-31) :

There was a certain rich man who was clothed in purple and fine linen and feasted sumptuously every day. And there was a certain beggar named Lazarus, who lay at his gate, full of sores, desiring to be filled with the crumbs that fell from the rich man’s table. And no one did give him: moreover the dogs came and licked his sores. And it came to pass that the beggar died and was carried by the angels into Abraham’s bosom. And the rich man also died…. And lifting up his eyes when he was in torments, he saw Abraham… and he cried and said: Father Abraham, have mercy on me…. And Abraham said to him; Son, remember that thou didst receive good things in thy lifetime, and likewise Lazarus evil things: but now he is comforted and thou art tormented.

This is to declare in effect that, where natural conditions are unequal, providence and justice will sometimes make up for it in the distribution of natural gifts. Again, the Gospel beatitudes tell us that one who is bereft of this world’s enjoyments will in some cases feel more powerfully drawn to the joys of the interior life. This is what our Lord would have us understand when He says: “Blessed are the poor in spirit…. Blessed are the meek… that suffer persecution for justice’ sake: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.” 138

The love of Jesus goes out to those servants of His nailed to the cross, because then they are more like Him through the effective oblation they make of their entire being for the salvation of sinners. In them He continues to live; in them He may be said to prolong down to the end of time His own prayers and sufferings, and above all His love, for perfect love consists in the complete surrender of self.

For some there comes a time when every road in life is barred against them; humanly speaking, the future holds out no prospect whatever to them. In some cases this is the moment when the call comes to something higher. Some there are who spend long years confined to a bed of pain; for these henceforth there is no way open but the way of holiness. 139

And so providence and justice, while giving to each one what is strictly necessary, will often make up for any disparity in natural conditions by the bestowal of grace. They reward us, even in this life, for the merits we have gained, reminding us, too, of our solemn duties by salutary warnings and well-deserved corrections, which are no more than medicinal punishments for the purpose of bringing us back into the right path. In this way will a mother correct her child if she loves it with a really enlightened, ardent love. When these salutary corrections are well received, we make expiation for our sins, and God takes the opportunity of inspiring us with a more sincere humility and a purer, stronger love. There is a sharp distinction between souls according to their willingness or unwillingness to listen to these warnings from God.

Providence and justice at the moment of death

As a general rule those who have paid heed during life to the warning of God’s justice and to the indefeasible right of the sovereign good to be loved above all things are not taken unawares when death comes, and in that supreme moment they find peace. Wholly otherwise is it usually with those who have refused to give ear to the divine warnings and who during life have confounded hope with presumption.

If there is one thing that is dependent on Providence, it is the hour of our death.” Be ye also ready, ” says our Lord, “for at what hour you think not the Son of man will come” (Luke 12: 40). The same is true of the manner of our death and the circumstances surrounding it. It is all completely unknown to us; it rests upon Providence, in which we must put all our trust, while preparing ourselves to die well by a better life.

Looked at from the point of view of divine justice, what a vast difference there is between the death of the just and that of the sinner! In the Apocalypse (20: 6, 14) the death of the sinner is called a “second death, ” for he is already spiritually dead to the life of grace, and if the soul departs from the body in this condition it will be deprived of that supernatural life forever. May God preserve us from that second death. The unrepentant sinner, says St. Catherine, 140 is about to die in his injustice, and appear before the supreme Judge with the light of faith extinguished in him, which he received burning in holy baptism (but which he has blown out with the wind of pride) and with the vanity of his heart, with which he sets his sails unfurled to all the winds of flattery. Thus did he hasten down the stream of the delights and dignities of the world at his own will, giving in to the seductions of his weak flesh and the temptations of the devil.

The remorse of conscience (which is not to be confused with repentance) is then aroused with such lively feelings, that it gnaws the very heart of the sinner, because he recognizes the truth of what at first he knew not, and his error is the cause of great confusion to him…. The devil torments him with infidelity in order to drive him to despair. 141

What are we to say of this struggle which finds the sinner disarmed, deprived of his living faith now extinguished in him, deprived also of a steadfast hope, which he has failed to foster as he ought by committing himself daily to God and laboring for Him? The wretched sinner has placed all his hopes in himself, not realizing that everything he possessed was but lent and must one day be accounted for. He is deprived, too, of the flame of charity, of the love of God which he has now utterly lost. He finds himself alone in his spiritual nakedness, bereft of all virtue. Having turned a deaf ear to the many warnings given during life, now, whichever way he turns, he sees nothing but cause for confusion. Due consideration was not given to divine justice during life; now it is the full weight of that justice which makes itself felt, while the enemy of all good seeks to persuade the sinner that for him henceforth there is no mercy. How we should pray for those who are in their agony! If we do, then others will pray for us when our last moment comes.

In those last moments mercy still accommodates itself to the sinner, as it did to Judas when our Lord said at the last supper (Matt. 26: 24) : “Woe to that man by whom the Son of man shall be betrayed. It were better for him, if that man had not been born.” Our Lord has not yet said who it is that is about to betray Him: He is too tender-hearted to reveal it. And then, the Gospel continues, “Judas that betrayed Him answering said: Is it I Rabbi? He saith to him: Thou hast said it.” In delaying to put the question until the rest of the Apostles had done so, Judas feigns innocence, as if that were possible with one who even in this world reads the secrets of the heart. Notice, says St. Thomas commenting on these words, with what gentleness Jesus continues to call him friend and answers: “Thou hast said it”; as if to say, “It is you, not I, who say so, who are revealing it.” Once again our Lord shows Himself full of compassion and mercy, closing His eyes to the sins of men so as to give them one more salutary warning and lead them to repentance. In Him are realized those touching words of the Scripture: “The Lord is compassionate and merciful” (Ps. 102: 8) ; “overlooking the sins of men for the sake of repentance” (Wis. 11: 24) ; “Let the meek hear and rejoice” (Ps. 33: 3).

In view of these final warnings from God, we may well ask how the sinner dare accuse God of being a tyrant. No, it is the sinner who is his own tyrant; it is the sinner who has no consideration for himself; and none for God either, since he refuses Him the joy of applying to him what He said of the prodigal: “This my son was lost and is found” (Luke 15: 24).

If the sinner will only disburden his conscience by a sincere confession, making acts of faith, of confidence in God, and contrition, at the last moment the divine mercy will enter in to temper justice and will save him. By reason of God’s mercy every man may cling to hope at death if he so wills, if he offers no resistance. Remorse will then give place to repentance.

Otherwise the soul succumbs to remorse and abandons itself to despair, a sin far more heinous than any of the preceding, as in that neither infirmity nor the allurements of sensuality can excuse, a sin by which the sinner esteems his wickedness as outweighing God’s divine mercy. And once in this despair, the soul no longer grieves over sin as an offense against God, it grieves only over its own miserable condition, a grief very different from that which characterizes attrition or contrition.

Blessed is the sinner who like the good thief then repents, reflecting that, as St. Catherine says, 142 “the divine mercy is greater without comparison than all the sins which any creature can commit.”

Happier still is the just soul that throughout life has given due thought to the loving fulfilment of duty and, after the merits won and the struggle sustained here on earth, yearns for death in order to enjoy the vision of God, even as St. Paul desired “to be dissolved and to be with Christ” (Phil. 1: 23).

As a rule a great peace fills the soul of the just in their last agony, a peace the more profound the greater their perfection; and this is often most true of those who during life have had the greatest dread of the divine justice. For them death is peaceful because their enemies have been vanquished during life. 143 Sensuality has been reduced to subjection under the curb of reason. Virtue triumphs over nature, overcoming the natural fear of death through the longing to attain their final end, the sovereign good. Being conformed to justice during life, conscience continues tranquil, though the devil seeks to trouble and alarm it.

At that moment, it is true, the value of this present time of trial, which is the price of virtue, will be more clearly seen, and the just soul will reproach itself for not having made better use of its time. But the sorrow it then experiences will not overwhelm it; it will be profitable in inducing the soul to recollect itself and place itself in the presence of the precious blood of our Savior, the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world. In the passage from time to eternity there is thus an admirable blending of God’s mercy and justice. In his dying moments the just man anticipates the bliss prepared for him; he has a foretaste of his destiny which may sometimes be seen reflected in his countenance.

God’s providence and justice in the next life

After death God’s providence and justice intervene forthwith in the particular judgment. Revelation tells us so in the parable of the wicked rich man and the beggar Lazarus, whose souls were judged once and for all the moment they quitted this earth. Equally clear is St. Paul’s teaching in more than one passage: “We must all be manifested before the judgment seat of Christ, that everyone may receive the proper things of the body, according as he hath done, whether good or evil”; 144 “I have a desire to be dissolved and to be with Christ”; 145 “I have finished my course…. As to the rest, there is laid up for me a crown of justice which the Lord the just judge will render to me in that day: and not only to me, but to them also that love His coming”; 146 “It is appointed unto man once to die, and after this the judgment.” 147

It was the universal belief of the early Church that the martyrs entered at once into heaven and that unrepentant sinners, like the bad thief, received their punishment immediately after death.

The nature of this particular judgment is to be explained from the condition of the soul when separated from the body. Once the body has been left behind, the soul has direct vision of itself as a spiritual substance, in the same way that the pure spirit has direct vision of itself, and in that instant it is made aware of its moral condition. It receives an interior illumination rendering all discussion useless. God passes sentence, which is then transmitted by conscience, the echo of God’s voice. The soul now sees plainly what is its due according to its merits and demerits, which then stand out quite distinctly before it. This is what the liturgy expresses symbolically in the Dies Irae: Liber scriptus proferetur, in quo totum continetur. The soul will see whatever has been written down in the book of life concerning it. 148

Justice will then mete out condign punishment for sins committed, to last for a time or for eternity. Mortal sin still unrepented at the moment of death will be henceforth like an incurable disease, but in something that cannot die, the immortal soul. The sinner has turned his back unrepentantly on the sovereign good, has in practice denied its infinite dignity as the last end, and has failed to revoke this practical denial while there was yet time. It is an irreparable disorder and a conscious one. Remorse is there, but without repentance; pride and rebellion will continue forever and with them the punishment they deserve. But above all it involves the perpetual loss of the divine life of grace and the vision of God, of supreme bliss, the sinner clearly realizing that through his own fault he has failed forever to attain his destined end. 149

Here the justice of God is seen to be infinite; it is a mystery that surpasses our understanding, as does the mystery of His mercy.

Here on earth the concepts or ideas we are able to have of divine justice and the rest of God’s perfections must always remain limited, confined, and that in spite of the correction we apply in denying all limitation. These concepts represent the divine attributes as distinct from one another, though we did say that there is no real distinction between them. It follows that these restricted ideas harden the spiritual features of God somewhat, as the human features are hardened when we attempt to reproduce them in little squares of mosaic. Our concept of justice being distinct from that of mercy, divine justice appears to us not only infinitely just but absolutely unyielding, and His mercy appears to be sheer caprice.

In heaven, however, we shall see how the divine perfections, even those to all appearances directly opposed, are intimately blended, identified in fact, yet without destroying one another in the Deity, in God’s intimate life, of which we shall then have distinct and immediate knowledge.

We shall then see that nowhere but in God do justice and mercy exist in their pure state, free from all imperfection, and that just as in us the cardinal virtues are interconnected and inseparable, so also in Him justice cannot exist unless it is united with mercy, and conversely there can be no such thing as mercy apart from justice and providence. 150

This is what is revealed to the saints from the moment of the particular judgment, which is immediately followed by their entry into glory.

There will be another manifestation of justice in the general judgment after the resurrection of the body, according to the words of the Creed: “I believe in Jesus Christ… who shall come to judge the living and the dead.” Our Lord tells us (Matt. 24: 30-46) : “All tribes of the earth… shall see the Son of man coming in the clouds of heaven with much power and majesty. And He shall send His angels with a trumpet and a great voice: and they shall gather together His elect from the four winds, from the farthest parts of the heavens to the utmost bounds of them.” If Jesus had not been the Son of God, how could He, a poor village artisan, have uttered such words as these? It would have been the height of foolishness, whereas everything goes to show that it is the essence of wisdom.

This general judgment is evidently expedient, because man is not merely a private person, but is a social being, and this judgment will reveal to all men the rectitude of Providence and its ways, the reason also of its decisions and their outcome. Divine justice will then appear in all its sovereign perfection in contrast to the frequent miscarriage of human justice. Infinite mercy will be revealed in the case of repentant and pardoned sinners. Every knee will bend before Christ the Savior, triumphant now over sin, the devil, and death. Then will appear also the glory of the elect: he who was humbled will now be exalted, and the kingdom of God will be established forever in the light of glory, in love and in peace. 151

This is the kingdom we long for when day by day we say in the Our Father: “Thy kingdom come, Thy will [signified to us in Thy precepts and in the spirit of the counsels] be done on earth as it is in heaven.” 152

26. Providence And Mercy¶

We have been considering the relations between providence and divine mercy in the distribution of the means necessary for all to attain their end, in rewarding merit and chastising sin and wickedness. It now remains for us to speak of providence in its relation to divine mercy. God’s mercy seems at first sight to differ so widely from His justice as to be directly contrary to it; it appears to set itself up in opposition to justice, intervening in order to restrict its rights. Yet in reality there can never be any opposition between two divine perfections; however widely they may differ from each other, the one cannot be the negation of the other. As we have already seen, they are so united in the eminence of the Deity, the intimate life of God, as to be completely identified.

Far from setting itself up in opposition to justice and putting restrictions upon it, mercy unites with it, but in such a way as to surpass it, as St. Thomas says. 153 In psalm 24: 10, we read: “All the ways of the Lord are mercy and truth (i. e., justice), ” but, adds St. James, “Mercy exalteth herself above judgment [justice].” 154 In what sense is this to be understood? Says St. Thomas: 155

In this sense, that every work of justice presupposes and is founded upon a work of mercy, a work of pure loving kindness, wholly gratuitous. If, in fact, there is anything due from God to the creature, it is in virtue of some gift that has preceded it…. If He owes it to Himself to grant us grace necessary for salvation, it is because He has first given us the grace with which to merit. Mercy (or pure goodness) is thus, as it were, the root and source of all the works of God; its virtue pervades, dominates them all. As the ultimate fount of every gift, it exercises the more powerful influence, and for this reason it transcends justice, which follows upon mercy and continues to be subordinate to it.

If justice is a branch springing from the tree of God’s love, then the tree itself is mercy, or pure goodness ever tending to communicate, to radiate itself externally.

We shall best understand this by a consideration of our own lives. Our best course will be to proceed, as we did with justice, by considering the relations between providence and mercy first of all in this present life, then at the moment of death, and lastly in the next life.

Providence and mercy in the course of our present life

If in this present life divine justice gives to each of us whatever is required for us to live rightly and so attain our end, mercy, on the other hand, gives far beyond what is strictly necessary, and it is in this sense that it surpasses justice.

In creating us, for example, God might have established us in a purely natural condition, endowing us with a spiritual, immortal soul, but not with grace. Out of pure goodness from the very day of creation He has granted us to participate supernaturally in His intimate life by bestowing on us sanctifying grace, the principle of our supernatural merits.

Again, after the fall, He might have left us in our fallen condition so far as justice is concerned. Or He might have raised us up from sin by a simple act of forgiveness conveyed through the mouth of a prophet after we had fulfilled certain conditions. But He has done something infinitely greater than this: out of pure mercy He gave us His only Son as a redeeming victim, and it is possible for us at all times to appeal to the infinite merits of the Savior. Justice loses none of its rights, but it is mercy that prevails.

Once Jesus had died for us, all we needed was to be guided by interior graces as well as by the preaching of the Gospel; but divine mercy has given us far more than this: it has given us the Eucharist, in which the sacrifice of the cross is perpetuated in substance on our altars and the fruits of that sacrifice are applied to our souls. 156

Finally, those of us who have been born into Christian and Catholic families have received incomparably more from the divine mercy than the bare essentials God has given to the savage of Central Africa. With those essentials God has given to the savage, provided the first prevenient graces are not resisted, the savage will receive whatever further graces are required for salvation; but we have received much more than this from our very childhood. When we consider the matter, we realize that we have been led on by the invisible hands of Providence and Mercy, preserving us from many a false step and raising up each one of us individually when we have fallen.

Again, if divine justice rewards the merits we have acquired even in this life, the gifts of mercy go far beyond anything we have deserved.

In the collect for the eleventh Sunday after Pentecost we pray: “Almighty and eternal God, who in the abundance of Thy goodness dost surpass the merits and even the desires of Thy suppliants: pour out Thy mercy upon us, forgive us the things our conscience must fear, and grant us what we cannot presume to ask. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, etc.” 157

The grace of absolution from mortal sin is not something that can be merited, it is a gratuitous gift. And how often has that grace been granted us!

Again, by no merit of ours could we obtain the grace of communion; it is the fruit of the sacrament of the Eucharist, which of itself produces that grace within us, even daily if we wish. And how many communions has not the divine mercy granted us! Let us bear in mind that if we are faithful in fighting against all attachment to venial sin, each successive communion becomes substantially more fervent than the last, since each successive communion must not only preserve but increase charity within us, thus disposing us to receive our Lord on the morrow with a substantial fervor, a readiness of desire not merely the same but more intense.

This law of acceleration governing the love of God in the souls of the just must, if we are alive to it, arouse our admiration. It will be seen that, just as the stone falls more rapidly as it approaches the earth which is attracting it, so is it with the souls of the just: the more nearly they approach to God and therefore the greater the force of His attraction, the more rapid must their progress be. We then grasp the meaning of these words of the psalm (32: 5) : “The earth is full of the mercy of the Lord.” Even the sinner can say with the psalmist: “Return, O Lord,… we are filled in the morning with Thy mercy: and we have rejoiced, and are delighted all our days” (Ps. 89: 14).

If we could only see the whole span of our life as it is written down in the book of life, how many instances should we find where providence and mercy have intervened to piece together again the chain of our merits which again and again perhaps we have broken by our sins! But at the final moment mercy intervenes in a manner no less gracious.

Providence and mercy at the moment of death

If at that moment justice alone were to enter in, all those who had led a life of sin would die as they had lived. After so many warnings from Providence had been neglected, the final warning would receive no better response; remorse would not give place to a salutary repentance. Thanks to the mercy of God, however, this last appeal is more insistent. If His justice inflicts the punishment due to sin, here again His mercy will outstrip it by pardoning. To pardon means to “give beyond” what is due. The rights of justice are safeguarded, but mercy outweighs it by constantly inspiring the sinner, as death approaches, to make a great act of love for God, and of contrition, which will wipe away sin and the eternal punishment mortal sin incurs. And so, through the intervention of mercy, through the infinite merits of the Savior, through the intercession of Mary refuge of sinners, and of St. Joseph patron of the dying, for many persons death is something very different from the way they lived. These are the laborers of the eleventh hour whom the Gospel parable speaks of (Matt. 20:9) ; they receive eternal life, as do the rest, in proportion to the few meritorious acts they have per formed before death, when already in their agony. Such was the death of the good thief who, touched by the loving kindness of Jesus dying on the cross, was converted, and he had the happiness of hearing from the Savior’s lips: “This day thou shalt be with Me in paradise” (Luke 23: 43).

These interventions of mercy at the moment of death are one of the sublimest features of the true religion. This was often clearly enough shown during the World War, when a man, dying a tragic death after absolution, was saved, who in ordinary circumstances, in the midst of his occupations and pleasures, would perhaps have been lost.

So, too, where there are Catholic hospitals, many a poor soul, heeding the warning that the disease from which he is suffering is soon to carry him off, there prepares himself for a happy death. He listens to some sister speaking to him on this subject and then to the priest who finally reconciles him to God after thirty or forty years of a life spent practically in indifference, a life that has left much to be desired.

The divine mercy extends appealingly to every one of the dying. Jesus said: “Come to Me, all you that labor and are burdened: and I will refresh you” (Matt. 11:28). He dies for all men: as the beautiful prayers for those in their agony remind us, He is the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world.

The death of the repentant sinner is one of the greatest manifestations of divine mercy. Some striking examples of it are given us in the life of St. Catherine of Siena written by her confessor, Blessed Raymund of Capua. 158 Two condemned criminals, who were being tortured with hot pincers, were blaspheming ceaselessly, and then through her prayers the unhappy wretches received a vision of our Lord, who appeared covered with wounds, inviting them to repent and promising them forgiveness. At that same moment they begged earnestly for a priest and with heartfelt contrition confessed their sins. Thereupon their blasphemies were turned to praise, and they went joyfully to their death as to the gateway of heaven. Those who witnessed the incident were struck with amazement and could assign no reason for such a sudden change in their interior dispositions.

On another occasion the saint herself was present at the execution of the young nobleman, Nicholas Tuldo, who had been condemned to death for criticizing the government. When she saw how desperately he clung to life, refusing to accept what seemed to him so unjust a punishment, she herself prepared his soul to appear before God. Her account of the death-scene is given in a letter to her confessor, Raymund of Capua:

Seeing me at the place of execution, he began to smile, and wanted me to make the sign of the cross upon him. I did so and then I said to him: “On your knees, sweetness my brother. You are going to the marriage feast. You are about to enter into everlasting life.” He prostrated himself with great gentleness, and I stretched out his neck; and bending over him, I reminded him of the blood of the Lamb. His lips said nought save “Jesus’, and “Catherine. ‘, And so saying, I received his head in my hands, closing my eyes in the divine goodness, and saying, “I will.”

Then I saw, as might the clearness of the sun be seen, the God-man, the wound in His side being open. He was permitting a transfusion of that blood with His blood, and adding the fire of holy desire given to that soul by grace to the fire of His divine charity. 159

But if the death of the sinner is a manifestation of the divine mercy, far more beautiful is the death of the saint who has always remained faithful. His last moments are, as a rule, peaceful because he has vanquished his enemies during life and his soul is now prepared for the passage to eternity. Uniting himself with all the masses then being celebrated, he makes of his death a last sacrifice of reparation, adoration, thanksgiving, and supplication to obtain thereby that last grace of final perseverance which carries with it the assurance of salvation.

Providence and mercy after death

Mercy and justice, the Scripture tells us (Ps. 24: 10), combine in every one of God’s works; but whereas mercy is the more prominent in some, as in the conversion of the sinner, in others justice predominates, as in the case of punishment due to sin.

Thus it is that, as St. Thomas says, 160 after death “mercy intervenes on behalf of the reprobate, in the sense that the punishment they receive is less than they deserve.” Were justice alone to enter in, they would suffer still more. St. Catherine of Siena is of the same mind. 161 Mercy is there to temper justice even for those who have fomented hatred among others, between class and class, nation and nation, even for the most perverse, for monsters like Nero, who have shown a refinement of malice, an obstinacy of will that spurned all advice.

Obviously, with the souls in purgatory divine mercy is still more active, inspiring them with the loving desire to make reparation, which tempers a little that keen purifying pain they are undergoing and confirms them in their assurance of salvation.

In heaven divine mercy shines forth in the saints according to the intensity of their love for God. Our Lord will greet them with the words recorded in St. Matthew (25: 34) :

Come, ye blessed of My Father, possess you the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world. For I was hungry, and you gave Me to eat: I was thirsty, and you gave Me to drink: I was a stranger, and you took Me in: naked, and you covered Me: sick, and you visited Me: I was in prison, and you came to Me. Then shall the just… answer Him saying: Lord, when did we see Thee hungry… thirsty… and came to Thee? And the King answering shall say to them: Amen I say to you, as long as you did it to one of these My least brethren, you did it to Me.

What joy will be ours in that first instant of our entering into glory, when we shall receive the light of glory in order to see God face to face, in a vision that will know no end, whose measure will be the unique instant of changeless eternity.

How consoling is the thought of this infinite mercy, which transcends all wickedness and is inexhaustible. For this reason no relapse into sin, however shameful, however criminal, should cause a sinner to despair. There can be no greater outrage against God than to consider His loving kindness inadequate to forgive. As St. Catherine of Siena tells us, “His mercy is greater without any comparison than all the sins which any creature can commit.” 162

In this matter we should keep before our minds these words from the psalms, words that the liturgy is constantly putting before us:

The mercies of the Lord I will sing forever…. For Thou hast said: Mercy shall be built up forever in the heavens. Thy truth shall be prepared in them…. Thou art mighty, O Lord, and Thy truth is round about Thee, Thou rulest the power of the sea…. Thou hast humbled the proud one….

The Lord is compassionate and merciful: longsuffering and plenteous in mercy. He will not always be angry: nor will He threaten forever…. For according to the height of the heaven above the earth, He hath strengthened His mercy toward them that fear Him…. As a father hath compassion on his children, so hath the Lord compassion on them that fear Him: for He knoweth our frame. He remembereth that we are dust.

Man’s days are as grass: as the flower of the field so shall he flourish. For the spirit shall pass in him, and he shall not be…. But the mercy of the Lord is from eternity and unto eternity, upon them that fear Him. 163

May the Lord deign that these words be revealed in us also, that we may glorify Him forever.

Rarely have the relations between mercy, justice, and providence been better expressed than in the Dies Irae. 164

Day of wrath and doom impending, David’s word with Sibyl’s blending! Heaven and earth in ashes ending! O, what fear man’s bosom rendeth, When from heaven the Judge descendeth, On whose sentence all dependeth! Death is struck, and nature quaking, All creation is awaking, To its Judge an answer making. Lo! the book exactly worded, Wherein all hath been recorded; Thence shall judgment be awarded. When the Judge His seat attaineth, And each hidden deed arraigneth, Nothing unavenged remaineth. King of Majesty tremendous, Who dost free salvation send us, Fount of pity, then befriend us! Think, kind Jesu! my salvation Caused Thy wondrous incarnation; Leave me not to reprobation. Faint and weary Thou hast sought me, On the cross of suffering bought me; Shall such grace be vainly bought me? Righteous Judge! for sin’s pollution Grant Thy gift of absolution, Ere that day of retribution. Through the sinful woman shriven, Through the dying thief forgiven, Thou to me a hope hast given. Low I kneel, with heart submission, Crushed to ashes in contrition; Help me in my last condition! Spare, O God, in mercy spare him! Lord all-pitying, Jesu blest, Grant them Thine eternal rest. Amen.

Let us acquire the habit of praying for those in their last agony, that the divine mercy may incline to them. Then others will assist us when the moment of our own death arrives. Where or how we shall die, we know not; it may be quite alone; but if we have prayed frequently for the dying, if again and again we have said with attention and from our hearts: “Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death, ” then at the supreme moment mercy will incline to us also. 165

27. Providence And The Grace Of A Happy Death¶

One of those vital questions that should be of the deepest interest to every soul, no matter what its condition, is the question of a happy death. On this subject St. Augustine wrote one of his last and finest works, the Gift of Perseverance, in which he gives his definite views on the mystery of grace.

By the Semi-Pelagians on the one hand and Protestants and Jansenists on the other, this vital question has been understood in widely different, even fundamentally opposite, senses. These two contrary heresies prompted the Church to define her teaching on this point more precisely and to declare the truth in all its sublimity as the transcendent mean between the extreme errors.

A brief summary of these errors will give us a better appreciation of the truth and a clearer understanding of what the grace of a happy death really is. We shall then see how this grace may be obtained.

The doctrine of the Church and the errors opposed to it

The Semi-Pelagians maintained that man can have the initium fidei et salutis, the beginning of faith and a good desire apart from grace, this beginning being subsequently confirmed by God. According to their view, not God but the sinner himself takes the first step in the sinner’s conversion. On the same principles the Semi-Pelagians maintained that, once justified by grace, man can persevere until death without a further special grace. For the just to persevere unto the end, it is enough, they said, that the initium salutis, this natural good will, should persist.

It amounted to this, that God not only wills all men to be saved, but wills it to the same extent in every case; and further, that precisely the element which distinguishes the just from the wicked—the initium salutis and those final good dispositions which are to be found in one and not in another, in Peter and not in Judas—is not to be referred to God as its author; He is simply an onlooker.

It meant the rejection of the mystery of predestination and the ignoring of those words of our Lord: “No man can come to Me, except the Father, who sent Me, draw him” (John 6: 44), words that apply both to the initial and to the final impulse of our hearts to God.” Without Me you can do nothing” (John 15: 5), our Lord said. As the Second Council of Orange recalled against the Semi-Pelagians, St. Paul added: “Who distinguisheth thee? Or what hast thou that thou hast not received?” (I Cor. 4:7) ; “Not that we are sufficient to think anything of ourselves, as of ourselves; but our sufficiency is from God” (II Cor. 3: 5). If this is true of our every thought, still more true is it of the least salutary desire, whether it be the first or the last.

St. Augustine, too, pointed out that both the first grace and the last are in an especial way gratuitous. The first prevenient grace cannot be merited or in any way be due to a purely natural good impulse, since the principle of merit is sanctifying grace, and this, as its very name implies, is a gratuitous gift, a life wholly supernatural both for men and for angels. Again, the final grace, the grace of final perseverance, is, as St. Augustine pointed out, a special gift, a grace peculiar to the elect, of whom our Lord said: “No one can snatch them out of the hand of My Father” (John 10: 29). When this grace is granted, he added, it is from sheer mercy; if on the other hand it is not given, it is as a just chastisement for sin, usually for repeated sin, which has alienated the soul from God. We have it exemplified in the death of the good thief and that of the unrepentant one.

For St. Augustine the question is governed by two great principles. The first is that not only are the elect foreseen by God, but they are more beloved by Him. St. Paul had said: “Who distinguisheth thee? Or what hast thou that thou hast not received?” (I Cor. 4:17.) Later on we find St. Thomas saying that “since the love of God is cause of whatever goodness there is in things, no one thing would be better than another, if God did not will a greater good for one than for the other” (Ia, q. 20, a. 3).

The other principle, formulated by St. Augustine in express terms, is that God never commands the impossible, though in commanding He admonishes us to do what we can and to ask for grace to accomplish what we ourselves cannot do: Deus impossibilia non jubet, sed in jubendo monet et facere quod possis et petere quod non possis. These words, taken from his De natura et gratia, 166 are quoted by the Council of Trent 167 and bring out how God desires to make it really possible for all to be saved and observe His precepts, and how in fact He does so. As for the elect, He sees to it that they continue to observe His precepts until the end.

How are these two great principles, certain and beyond dispute, to be intimately reconciled? Before receiving the beatific vision, no created intellect, of men or of angels, can perceive how this can be. It must first be seen how infinite justice, infinite mercy, and a sovereign liberty are reconciled in the Deity, and this requires an immediate vision of the divine essence.

As we know, these principles laid down by St. Augustine against Semi-Pelagianism were in substance approved by the Second Council of Orange. Thus it remains true that the grace of a happy death is a special grace peculiar to the elect.

At the opposite extreme to Semi-Pelagianism, Protestantism and Jansenism distorted the first principle formulated by St. Augustine by rejecting the second. On the pretext of emphasizing the mystery of predestination, they denied the all embracing character of God’s saving will, maintaining also that in some cases God commands the impossible, that at the moment of death it is not possible for all to be faithful to the divine precepts. We know what the first proposition of Jansenius was, 168 that certain of God’s commandments are impossible for some even among the just, and this not merely when they are negligent or have not the full use of reason and will, but even when they have the desire to carry out these precepts and do really strive to fulfil them: justis volentibus et conantibus. Even for them the carrying out of certain precepts is impossible because they are denied the grace that would make it possible.

Such a proposition must drive men to despair and shows how wide is the gulf separating Jansenism from the true doctrine of St. Augustine and St. Thomas: Deus impossibilia non jubet. This grave error involves the denial of God’s justice and hence of God Himself; a fortiori it denies His mercy and the offering of sufficient grace to all. Indeed it means the rejection of true human liberty (libertas a necessitate), so that finally sin becomes unavoidable and is sin no longer, and hence cannot without extreme cruelty be punished eternally.

From the same erroneous principles, Protestants were led to declare not only that predestination is gratuitous, but that good works, in the case of adults, are not necessary for salvation, faith alone sufficing. Hence that saying of Luther’s: Pecca fortiter et crede fortius: sin resolutely, but trust even more resolutely in the application of Christ’s merits to you and in your predestination. This is no longer hope, but is an unpardonable presumption. Jansenism and Protestantism, in fact, oscillate between presumption and despair, without ever being able to find true Christian hope and charity.

Against this heresy the Council of Trent defined 169 that “Whereas we should all have a steadfast hope in God, nevertheless (without a special revelation) no one can have absolute certainty that he will persevere to the end.” The Council quotes the words of St. Paul: “Wherefore, my dearly beloved (as you have always obeyed…), with fear and trembling work out your salvation…. For it is God who worketh in you, both to will and to accomplish according to His good will” (Phil. 2: 12) ; “He that thinketh himself to stand, let him take heed, lest he fall” (I Cor. 10: 12). He must put all his trust in the Almighty, who is alone able to raise him up when he has fallen and keep the just upright in a corrupt and perverse world.” And he shall stand: for God is able to make him stand” (Rom. 14: 4).

And so the Church maintains the Gospel teaching in its rightful place above the vagaries of error, above the extreme heresies of Semi-Pelagianism and Protestantism. On the other hand, the elect are more beloved of God than are others and, on the other hand, God never commands the impossible, but in His love desires to make it really possible for all to be faithful to His commandments.

It remains true therefore, as against Semi-Pelagianism, that the grace of a happy death is a special gift 170 and, as against Protestantism and Jansenism, that among those who have the use of reason they alone are deprived of help at the last who actually reject it by resisting the sufficient grace offered them, as the bad thief resisted it, and that in the very presence of Christ the Redeemer. 171

This being so, how are we to obtain this immense grace of a happy death? Can we merit it? And if it cannot be merited in the strict sense, is it possible for us at any rate to obtain it through prayer? What are the conditions that such a prayer must conform to?

These are the two points we wish to develop, relying especially on what St. Thomas has written about them in Ia IIae, q. 114, a. 9.

Can we merit the grace of a happy death?

Are we able to merit it in the strict sense of the term “merit, ” which implies the right to a divine reward?

Final perseverance, a happy death, is no more than the continuance of the state of grace up to the moment of death, or at any rate it is the coincidence or union of death and the state of grace if conversion takes place at the last moment. In short, a happy death is death in the state of grace, the death of the predestinate or elect.

We now see why the Second Council of Orange declared it to be a special gift, 172 why, too, the Council of Trent declared the gratuitous element in it by saying that, “this gift cannot be derived from any other but from the One who is able to establish him who standeth that he stand perseveringly, and to restore him who has fallen.” 173

Whatever we are able to merit, though it comes chiefly from God, is not from Him exclusively; it proceeds also from our own merits, which imply the right to a divine reward. Hence we feel that the just must humbly admit that they have really no right to the grace of final perseverance.

St. Thomas demonstrates this truth by a principle as simple as it is profound, one that is now commonly received in the Church 174 (cf. Ia IIae, q. 114, a. 9). We may profitably pause to consider it for a moment; it will serve to keep us humble.

“The principle of merit, ” says St. Thomas, “cannot itself be merited (principium meriti sub merito non cadit) “; for no cause can cause itself, whether it be a physical cause or moral (as merit is). Merit, that act which entitles us to a reward, cannot reach the principle from which it proceeds. Nothing is more evident than that the principle of merit cannot itself be merited.

Now the gift of final perseverance is simply the state of grace maintained up to the moment of death, or at least at that moment restored. Furthermore, the state of grace, produced and maintained by God, is in the order of salvation the very principle of merit, the principle rendering our acts meritorious of an increase in grace and of eternal life. Apart from the state of grace, apart from charity whereby we love God with an efficacious love, more than ourselves, with a love founded at least on a right estimation of values, our salutary acts have no right to a supernatural reward. In such case these salutary acts, like those preceding justification, bear no proportion to such a reward; they are no longer the actions of an adopted son of God and of one who is His friend, heir to God and coheir with Christ, as St. Paul says. They proceed from a soul still estranged from God the last end, through mortal sin, from one having no right as yet to eternal life. Hence St. Paul writes (I Cor. 13: 1-3) : “If I have not charity, I am nothing… it profiteth me nothing.” Apart from the state of grace and charity, my will is estranged from God, and personally therefore I can have no right to a supernatural reward, no merit in the order of salvation.

Briefly, then, the principle of merit is the state of grace and perseverance in that state; but the principle of merit cannot itself be merited.

If the initial production of sanctifying grace cannot be merited, the same must be said of the preservation of anyone in grace, this being simply the continuation of the original production and not a distinct divine action. So says St. Thomas (Ia, q. 104, a. 1 ad 4um) : “The conservation of the creature by God is not a fresh divine action, but the continuation of the creative act.” Hence the maintenance of anyone in the state of grace can no more be merited than its original production.

To this profound reason many theologians add a second, which is a confirmation of it. Strictly condign merit (meritum de condigno) or merit founded in justice presupposes the divine promise to reward a certain good work. But God has never promised final perseverance or preservation from the sin of final impenitence to one who should keep His commandments for any length of time. Indeed it is precisely this obedience until death in which final perseverance consists; hence it cannot be merited by that obedience, for otherwise it would merit itself. We are thus brought back to our fundamental reason, that the principle of merit cannot be merited. Moreover, with due reservations, the same reason is applicable to congruous merit (meritum de congruo), that merit which is founded in the rights of friendship uniting us to God, the principle of which is again the state of grace. 175

What it all comes to is this, that God’s mercy, not His justice, has placed us in the state of grace and continues to maintain us therein.

The just, it is true, are able to merit eternal life, this being the term, not the principle of merit. Even so, if they are to obtain eternal life, it is still required that the merits they have won shall not have been lost before death through mortal sin. Now no acts of charity we perform give us the right to be preserved from mortal sin; it is mercy that preserves us from it. Here is one of the main foundations of humility.

Against this doctrine, now commonly accepted by theologians, a somewhat specious objection has been raised. It has been said that one who merits what is greater can merit what is less. Hence, since the just can merit eternal life de condigno and since this is something more than final perseverance, it follows that they can merit final perseverance also.

To this St. Thomas replies (ibid., ad 2um et 3um) : One who can do what is greater can do what is less, other things being equal, not otherwise. Now here there is a difference between eternal life and final perseverance: eternal life is not the principle of the meritorious act, far from it; eternal life is the term of that act. Final perseverance, on the other hand? is simply the continuance in the state of grace, and this, as we have already seen, is the principle of merit.

But, it is insisted, one who can merit the end can merit also the means to that end; but final perseverance is a means necessary to obtain eternal life and, therefore, like eternal life, can be merited.

Theologians in general reply by denying that the major premise is of universal application. Merit, indeed, is a means of obtaining eternal life, and yet it is not itself merited: it is enough that it can be had in other ways. Similarly, the grace of final perseverance can be obtained otherwise than by merit; it may be had through prayer, which is not directed to God’s justice, as merit is, but to His mercy.

But, it is further insisted, if final perseverance cannot be merited, neither can eternal life, which is only the consequence of this. From what has already been said, we must answer that anyone in the state of grace may merit eternal life only on condition that the merits he has gained have not been lost or have been mercifully restored through the grace of conversion. Hence the Council of Trent states (Sess. VI, cap. 16 and can. 32), that the just man can merit eternal life, si in gratia decesserit, if he dies in the state of grace.

We are thus brought back to that saying of St. Augustine and of St. Thomas after him: where the gift of final perseverance is granted, it is through mercy; if it is not granted, it is in just chastisement for sin, and usually for repeated sin, which has alienated the soul from God.

From this we deduce many conclusions, both speculative 176 and practical. We shall draw attention only to the humility that must be ours as we labor in all confidence to work out our salvation.

What we have been saying is calculated from one point of view to inspire dread, but what we have still to say will give great consolation.

How the grace of a happy death may be obtained through prayer

What are the conditions to which this prayer must conform? If, strictly speaking, the gift of final perseverance cannot be merited, since the principle of merit does not merit itself, it may nevertheless be obtained through prayer, which is directed not to God’s justice but to His mercy.

What we obtain through prayer is not always merited: the sinner, for example, who now is in the state of spiritual death, is able with the aid of actual grace to pray for and obtain sanctifying or habitual grace, which could not be merited, since it is the principle of merit.

It is the same with the grace of final perseverance: we cannot merit it in the strict sense, but we can obtain it through prayer for ourselves, and indeed for others also (cf. St. Thomas, ibid., ad Ium). What is more, we can and indeed we ought to prepare ourselves to receive this grace by leading a better life.

Whatever the Quietists may have said, failure to ask for the grace of a happy death and to prepare ourselves to receive it argues a disastrous and stupid negligence, incuria salutis.

For this reason our Lord taught us to say in the Our Father: “Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil”; and the Church bids us say daily: “Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death. Amen.”

Can our prayer obtain this grace of a happy death infallibly? Relying on our Lord’s promise, “Ask and you shall receive, ” theology teaches that prayer made under certain conditions is infallible in obtaining the gifts necessary for salvation, including therefore the final grace. What are the conditions required that prayer shall be infallibly efficacious? “They are four, ” St. Thomas tells us (IIa IIae, q. 83, a. 15 ad 2um) : “We must ask for ourselves, the things necessary for salvation, with piety, with perseverance.”

We are, in fact, more certain of obtaining what we ask for ourselves than when we pray for a sinner, who perhaps is resisting grace at the very moment we are praying for him. 177 But even though we ask for the gifts necessary for salvation, and for ourselves, prayer will not be infallibly efficacious unless it is made with piety, humility, and confidence, as well as with perseverance. Only then will it express the sincere, profound, unwavering desire of our hearts. And here once again together with our own frailty, appears the mystery of grace; we may fail to persevere in our prayer as we may fail in our meritorious works. This is why we say before communion at mass: “Never permit me, O Lord, to be separated from Thee.” Never permit us to yield to the temptation not to pray; deliver us from the evil of losing the relish and desire for prayer; grant us that we may persevere in prayer notwithstanding the dryness and the profound weariness we sometimes experience.

Our whole life is thus shrouded in mystery. Every one of our salutary acts presupposes the mystery of grace; every one of our sins is a mystery of iniquity, presupposing the divine permission to allow evil to exist in view of some higher good purpose, which will be clearly seen only in heaven.” The just man liveth by faith” (Rom. 1: 17). We need help to the very end, not only that we may merit, but that we may pray even. How are we to obtain the necessary help to persevere in prayer? By bearing in mind our Lord’s words: “If you ask the Father anything in My name, He will give it to you. Hitherto you have not asked anything in My name” (John 16: 23-24).

We must pray in the name of our Savior. That is the best way of purifying and strengthening our intention, and will do more than the sword of Brennus to turn the balance. We must ask Him besides to make personal intercession on our behalf. This intercession of His is continued from day to day in the holy mass, wherein, as the Council of Trent says, through the ministry of His priests He never ceases to offer Himself and apply to us the merits of His passion.

Seeing that the grace of a happy death can be obtained only through prayer and not merited, we should turn to that most excellent and efficacious of all prayers, the prayer of our Lord, principal Priest in the sacrifice of the mass. It was for this reason Pope Benedict XV, in a letter to the director of the Archconfraternity of Our Lady For a Happy Death, earnestly recommended the faithful to have masses offered during life for the grace of a happy death. This is indeed the greatest of all graces, the grace of the elect; and if at that last moment we unite ourselves by an intense act of love with Christ’s sacrifice perpetuated on the altar, we may even obtain remission of the temporal punishment due to our sins and thus be saved from purgatory.

Therefore, to obtain this grace of final perseverance, we should frequently unite ourselves with the Eucharistic consecration, the essence of the sacrifice of the mass, pondering on the four ends of sacrifice: adoration, supplication, reparation, and thanksgiving. Let us bear in mind that in this continuous oblation of Himself, our Lord is offering, as well the whole of His mystical body, especially those who suffer spiritually and thereby share a little in His own sufferings. This is a path that will carry us far if only we follow it perseveringly. 178

This practice of uniting ourselves with the sacrifice of the mass, with the masses that all day long are being celebrated wherever the sun is rising upon the earth, is the best preparation for a happy death, the best preparation for that hour when for the last time in our lives we shall unite ourselves with the masses then being celebrated far and near. United then with the sacrifice of Christ perpetuated in substance upon the altar, our death will itself be a sacrifice of adoration both of God’s supreme dominion, who is master of life and death, and of the majesty of Him who “leadeth down to hell and bringeth up again” (Tob. 13: 2). It will be a sacrifice of supplication to obtain the final grace both for ourselves and for those who are to die in that same hour. It will also be a sacrifice of reparation for the sins of our life, and a sacrifice of thanksgiving for all the favors we have received since our baptism.

The sacrifice we thus offer with a burning love for God may well open to us forthwith the gates of heaven, as it did for the good thief dying there by the side of our Lord as He brought to its close the celebration of His bloody mass, the sacrifice of the cross.

Before this last hour of our life comes, we should cultivate the practice of praying for the dying. At the door of some chapels may be seen the little inscription: Pray for those who are to die while holy mass is being offered. A certain French writer was one day much struck by this inscription and thereafter every day prayed for the dying while he was attending mass. Later on he was overtaken by a serious illness, which lasted for years; unable any longer to go to mass, he offered up his sufferings each morning for those who were to die in the course of the day. He thus had the joy of obtaining a number of unexpected conversions in extremis. 179

Let us also pray for the priests who assist the dying. It is a sublime ministry to assist a soul in its agony, in that last struggle. Pray that the priest may arrive in time and, if the sick man is already sunk in profound torpor, that he may obtain from heaven the necessary moment of consciousness. Pray that the priest may be able to prompt the sick man to make the great sacrifices God demands of him and that by his priestly prayer, offered in the name of Christ, in the name of Mary and of all the saints, he may obtain for him the final grace, the grace of graces.

As the priest is giving this assistance to the dying, he sometimes has the immense consolation of looking on, as it were, and watching our Lord save the soul as it suffers in that last moment. Hitherto perhaps he has prayed for a cure, but now that he sees the soul well prepared for death he ends by reciting confidently and with great peace that beautiful prayer of the Church:

Kyrie eleison, Christe eleison, Kyrie eleison…. Proficiscere, anima christiana, de hoc mundo, in nomine Dei Patris omnipotentis, qui te creavit, in nomine Jesu Christi Filii Dei vivi, qui pro te passus est, in nomine Spiritus Sancti, qui in te effusus est (“Go forth from this world, O Christian soul, in the name of God the Father Almighty, who created thee; in the name of Jesus Christ, Son of the living God, who suffered for thee; in the name of the Holy Ghost, who was poured out upon thee; in the name of the holy and glorious Virgin Mary, Mother of God; in the name of Blessed Joseph, predestined spouse of the Virgin; in the name of the angels and archangels… ; in the name of the patriarchs and prophets; in the name of the Apostles and the Evangelists; in the name of the holy martyrs and confessors; and of all the saints of God. May thy place be this day in peace and thy abode in holy Sion, through Our Lord Jesus Christ.

The mystery of salvation

And so for us a holy death throws light on the mystery of predestination, that terrible and yet gracious mystery which concerns the choice of the elect.

We now have a better grasp of those two great principles formulated by St. Augustine and St. Thomas which we quoted at the beginning of the chapter.

On the one hand, “since God’s love is the cause of things, no one thing would be better than another, if God did not will a greater good for one than for the other.” 180 No one thing would be better than another by reason of some salutary act, whether it be the first or the last, easy or difficult, in its inception or continuance, were he not more beloved of God. This is what our Lord refers to when He says of the elect, that “no man can snatch them out of the hand of My Father” (John 10: 29). He was speaking here of the efficacy of grace, which also led St. Paul to ask, “Who distinguisheth thee? Or what hast thou that thou hast not received?” (I Cor. 4:7.) Could we find anywhere a more profound lesson in humility?

On the other hand, God never commands the impossible, but love constrains Him to make the fulfilment of His precepts really possible for all, and especially for the dying; final grace is denied them only when they reject it by resisting the final appeal.

And therefore, say St. Augustine and St. Thomas, when the grace of final perseverance is granted, as it was to the good thief, it is through mercy; if it is not granted, it is as a just chastisement for sin and usually for repeated sin; it is a just chastisement, too, for the final act of resistance, as it was with the impenitent thief, who was lost even as he hung dying by the side of his Redeemer.

In the words of St. Prosper quoted by a council of the ninth century, “If some are saved, it is the gift of Him who saves; if some perish, it is the fault of them that perish.” 181

Absolutely certain as are these two great principles when considered apart—the efficacy of grace and the possibility for all to be saved—how are they infinitely reconciled one with the other? Here is St. Paul’s answer: “O the depth of the riches of the wisdom and of the knowledge of God! How incomprehensible are His judgments, and how unsearchable His ways!” (Rom. 11: 33.) No created intellect can perceive this intimate reconciliation before receiving the beatific vision. To perceive that is to perceive also how infinite justice, infinite mercy and a sovereign liberty are united and identified without any real distinction in the Deity, the intimate life of God, in precisely what is unutterable in Him, in that perfection which is exclusively His own and naturally incommunicable to creatures—in the Deity as it transcends being, unity, truth, goodness, intelligence, and love. For in all these absolute perfections creatures can participate naturally, whereas participation in the Deity is possible only through sanctifying grace, which is a participation in the divine nature not simply as intellectual life, but as a life strictly divine and the principle of that immediate vision and of that love which God has for Himself. 182

That we may perceive how the two principles of which we are speaking are intimately reconciled with each other, we must have immediate vision of the divine essence.

The more certain we are of the truth of these two principles, the more striking by contrast is the obscurity, the light-transcending obscurity, enveloping the heights of God’s intimate life in which they are united. They are like the two extremities of a dazzling are disappearing above into what the mystics call the great darkness, which is none other than that light inaccessible in which God dwells (I Tim. 6: 16).

This, though very imperfectly expressed, is to our mind the subject of Augustine’s speculation, or rather let us say of his contemplation, and it is the constant source of inspiration to St. Thomas in these difficult questions. The divine obscurity here mentioned is far beyond the reach of speculative theology; it is the proper object of faith (fides est de non visis), of faith illumined by the gifts of understanding and wisdom (fides donis illustrata).

From this higher standpoint, the contemplation of this terrible yet gracious mystery brings peace. Penetrated through and through with this doctrine, Bossuet writes as follows to one tormented with all sorts of ideas about predestination:

When such thoughts come into the mind, when all our efforts to dissipate them have proved vain, we should end by abandoning ourselves to God, with the assurance that our salvation is infinitely more secure in God’s hands than in our own. Only thus shall we find peace. All teaching about predestination should end in this; this should be the effect produced in us by our sovereign Master’s secret, a secret we should adore without pretending to sound its depths. We must lose ourselves in the heights and impenetrable depths of God’s wisdom, must cast ourselves into the arms of His immense loving kindness, looking to Him for everything, yet without unburdening ourselves of that care for our salvation which He demands of us…. The result of this tormenting must be the abandonment of yourself to God, who by reason of His loving kindness and the promises He has made will then be bound to watch over you. This, while the present life lasts, must be the final solution to all those questions about predestination which beset you; henceforth you must find your repose not in yourself but solely in God and His fatherly loving kindness.” 183

Bossuet, speaking in the same strain in one of the finest chapters of his Meditations sur l’Evangile (Part II, 72d day), says:

The proud man fears that unless he retains his salvation in his own hands, it is rendered too insecure; but in this he deceives himself. Can I find any security in myself? O my God, I feel my will escaping me at every moment, and even wert Thou willing to make me the sole master of my fate, I should refuse a power so dangerous to my weakness. Let it not be said that this doctrine of grace and predilection will bring pious souls to despair. How can anyone imagine he will give me greater assurance by throwing me back upon myself, by delivering me up to my own inconstancy? No, my God, I will have none of it. I can find no security except in abandoning myself to Thee. And this security is the greater when I reflect that those in whom Thou dost inspire this confidence, this complete self-abandonment to Thee, receive in this gentle prompting the highest mark of Thy loving kindness that can be had here on earth.

As we have shown elsewhere, 184 this to us seems to be the true mind of St. Augustine at its loftiest, when finally he soars above all reasoning, and comes to rest in the divine obscurity where the two aspects of the mystery, to all appearances diametrically opposed, must at last be reconciled. As formulated in the two principles—God never commands the impossible; no one would be better than another, were he not more beloved of God—these two aspects of the mystery are as two stars of the first magnitude shining brightly in the dark night of the spirit, yet wholly inadequate to reveal to us the uttermost depths of the firmament, the secret of the Deity.

Until we are given the beatific vision, grace by a secret instinct allays all our fears as to the intimate reconciliation of infinite justice and infinite mercy in the Deity, and this it does because it is itself a participation in the Deity, the light of life far surpassing the natural light of either the angelic or the human intellect.

Doubtless the whole of our interior life, every one of our actions, are shrouded in mystery; for every salutary act presupposes the mystery of grace from which it proceeds, and all sin is a mystery of iniquity, presupposing the divine permission that evil shall exist in view of some higher good purpose which will often escape us and will be clearly seen only in heaven. But in this obscurity characteristic of faith and also of contemplation here on earth, we are reassured when we remember that God’s will is to save, that Christ has died for us, that His sacrifice is perpetuated in substance on the altar, and that our salvation is more secure in His hands than it would be in ours, since we are more certain of the rectitude of the divine intentions than of our own, even the best of them.

Let us abandon ourselves in all confidence and love to His infinite mercy: there can be no better way of ensuring His condescending mercy toward us at this moment and above all at the hour of our death.

Let us frequently call to mind those beautiful words of the psalm, recurring each week in Thursday’s office of Tierce: “Cast thy care upon the Lord, and He shall sustain thee: He shall not suffer the just to waver forever” (Ps. 54: 23).

Let us call to mind the beautiful canticle of Tobias: “Thou art great, O Lord, forever, and Thy kingdom is unto all ages. For Thou scourgest, and Thou savest: Thou leadest down to hell, and bringest up again. He hath chastised us for our iniquities: and He will save us for His own mercy” (Tob. 13: 1).

In this self-abandonment we shall find peace. As our Lord hung dying for us, He experienced in His holy soul the keenest suffering our sins had caused, yet likewise the profoundest peace. So, too, in every Christian death, as in that of the good thief, there is suffering, a holy fear and trembling before the infinite justice of God, and a profound peace, a most intimate union prevailing between them. Nevertheless it is peace, the tranquillity that comes of true order, which predominates, as is apparent from these words of our Lord as He died: ‘It is consummated…. Father, into Thy hands I commend My spirit” (Luke 23: 46).

28. Providence And Charity Toward Our Neighbor¶

In the preceding chapter we saw how one of the greatest means in the workings of providence is charity toward our neighbor, by which all men should be united for their mutual aid in their progress toward the common goal, eternal life.

This subject is always of the greatest interest and we should often revert to it, especially in this age when charity toward others is summarily rejected by individualism in all its forms and completely distorted by the humanitarianism of the communist and internationalist.

Individualism aims at nothing higher than the search for what is useful and pleasurable to the individual or at most to the restricted group to which the individual belongs. Hence the bitter strife arising sometimes among members of the same family, but especially between classes and races or nations. Hence arise jealousy and envy, discord and hatred, and the most profound disruptions. It implies a complete disregard for the common good in its different degrees and an almost exclusive assertion of individual or particular rights.

In opposition to this, communist and internationalist humanitarianism lays so much stress on the rights of humanity as a whole, which in some degree is identified with God in a pantheistic sense, that the rights of individuals, families, and nations disappear altogether. On the pretext of promoting unity, harmony, and peace, the way is prepared for appalling confusion and disorder, like that which has prevailed in Russia since the revolution. To desire that all the parts in an organism shall have the perfection of the head, or to do away with the head because it is more perfect than the members, is to destroy the organism altogether.

Obviously the truth lies within these two extreme errors, yet transcends them. Equally remote from both individualism and communism, it affirms the rights inherent in the individual, in families, and in nations, and at the same time the claims of the common good, which is above every particular good. Thus a right estimation of things will safeguard the welfare of the individual through two kinds of justice: commutative, regulating the mutual dealings between one private party and another, and distributive, which sees to a fair distribution of general utilities and burdens. Also it will safeguard the common good through legal justice providing for the enactment of just laws and their observance, and again through equity, which looks to the spirit of the law in those exceptional cases where the letter of the law cannot be applied.

Admirably differentiated by Aristotle and well developed by St. Thomas in his treatise De justitia (IIa IIae, q. 58, 61, 120), these four kinds of justice (commutative, distributive, and legal or social justice, and equity) suffice in a way to preserve the just mean between the opposing errors of individualism and communist humanitarianism. St. Thomas’ teaching on this question is too little known and might well be made the subject of a series of interesting and useful studies.

However perfect this fourfold justice may become, even when enlightened by Christian faith, it can never attain the perfection that distinguishes charity toward God and our neighbor, the formal object of which is incomparably on a higher plane.

Let us recall what the primary object of charity is and what is its secondary object. We shall then see how we are to practice charity toward our neighbor and what part it plays in the fulfilment of the plan of Providence.

The primary object and formal motive of charity

The primary object of charity is something far above the distinctive good of the individual, far above the good of the family, of country, even of humanity. It is God, to be loved above all things, even more than ourselves, since His goodness is infinitely greater than our own. That is the first commandment: “Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with thy whole heart and with thy whole soul and with all thy strength and with all thy mind” (Luke 10: 27).

To this supreme commandment, all the other commandments and all the counsels are subordinate. Though it belongs to the supernatural order, nevertheless it corresponds to a natural inclination, to the primordial inclination of nature both in ourselves and in a certain sense in every creature.

Of course, innate in us is the instinct for self-preservation, the instinct, too, for the preservation of the species, the inclination to defend family and country, to love our fellows. But deeper still, as St. Thomas has shown (Ia, q. 60, a. 5) in our nature is the inclination prompting us to love more than ourselves God the very author of our nature. Why should this be? Because whatever by its very nature belongs to another, as the part belongs to the whole, the hand to the body, is naturally inclined to love that other more than itself: thus the hand will voluntarily sacrifice itself to protect the body. Now every creature, and in all that it is, is necessarily dependent upon God the Creator and Conserver of our being; hence every creature is inclined naturally, each after its own fashion, to love its Creator more than itself.