PART III : PROVIDENCE ACCORDING TO REVELATION¶

14. The Notion Of Providence¶

Having spoken of those divine perfections which the notion of providence presupposes, we must go on to consider in what this providence consists. What revelation has told us about God’s wisdom and His love will give us a clearer insight into its teaching concerning the divine governance. This teaching far surpasses that of the philosophers, many of whom maintain that providence does not extend beyond the general laws governing the universe; that it does not reach down to individuals and the details of their existence, to future free actions and the secrets of the heart. On the other hand, certain heretics have held that since providence extends infallibly to the least of our actions, there can be no such thing as liberty. The revealed teaching is the golden mean lying between these two extreme positions and transcending them.

Providence, as we shall see, is a sort of extension of God’s wisdom, which “reacheth from end to end mightily and ordereth all things sweetly” (Wis. 8: I; 14: 3).” Since, ” says St. Thomas, “God is the cause of all things by His intellect (in conjunction with His will), it is necessary that the type of the order of things toward their end should pre-exist in the divine mind; and the type of things ordered toward an end is, properly speaking, providence” (Ia, q. 22, a. 1). 29 As for the divine governance, though the expression is generally used as synonymous with providence, it is, strictly speaking, the execution of the providential plan (ibid., ad 2um).

St. Thomas (ibid.) also points out that providence in God corresponds to the virtue of prudence in us, which regulates the means with a view to the attainment of some end, which exercises foresight in anticipation of the future. We have, besides a purely personal prudence, that higher prudence which a father must exercise to provide for his family’s needs, and higher still, the prudence demanded in the head of the state that should be found in our law makers and other government officials for the promotion of the common interests of the nation. Likewise in God there is a providence directing all things to the good of the universe, the manifestation of the divine goodness in every order, from the inanimate creation even to the angels and saints in heaven.

And so by a comparison with the virtue of prudence is formed the analogical notion of providence, a notion accessible to commonsense reason and abundantly confirmed by revelation. A prudent person will first desire the end and then, having decided on the means to be employed, will begin using them; thus the end, which held first place in his desire, is the last in actual attainment. So we look upon God as intending from all eternity first the end and purpose of the universe and then the means necessary for the realization or attainment of that end. This commonsense view is expressed by the philosophers when they say that the end is first in the order of intention but last in order of execution. This point is of paramount importance when we are considering the end and purpose of the universe of material and spiritual beings.

From this general notion of providence we deduce its characteristics. We will briefly indicate them here before looking for a more vivid and detailed account of them in Scripture.

1) The absolute universality of providence is deduced from the absolute universality of divine causality, which in this case is the causality of an intellectual agent.” The causality of God, ” says St. Thomas, “extends to all beings, not only as to the constituent principles of species, but also as to the individualizing principles (for these also belong to the realm of being) ; it extends not only to things incorruptible but also to those corruptible. Hence all things that exist in whatsoever manner are necessarily directed by God toward some end” (Ia, q. 22, a. 2). This is demanded by the principle of finality, which states that every agent acts for some end and the supreme agent for the supreme end known to Him, to which He subordinates all else. That end, as we saw when speaking of the love of God, is the manifestation of His goodness, His infinite perfection, and His various attributes.

As we shall see, it is constantly asserted in the Old and New Testaments that the plan of providence has been fixed immediately by God Himself down to the last detail. His practical knowledge would be imperfect, were it not as far reaching as His causality, and without that causality nothing comes into existence. Obviously, therefore, as was stated above, any reality or goodness in creatures and their actions is caused by God. This means that with the exception of evil (that privation and disorder in which sin consists), all things have God as their first if not exclusive cause. 30 As for physical evil and suffering, God wills them only in an accidental way, in view of a higher good. 31 From the absolute universality of providence we deduce a second characteristic.

2) This universal and immediate sway exerted by providence, does not destroy, but safeguards the freedom of our actions. Not only does it safeguard liberty, but actuates it, 32 for the precise reason that providence extends even to the free mode of our actions, which it produces in us with our co-operation; for this free mode in our choice, this indifference dominating our desire, is still within the realm of being, and nothing exists unless it be from God. 33 The slightest idiosyncrasy of temperament and character, the consequences of heredity, the influence exerted on our actions by the emotions —all are known to providence; it penetrates into the innermost recesses of conscience, and has at its disposal every sort of grace to enlighten, attract, and strengthen us. There is thus a gentleness in its control that yields nothing to strength. Suaviter et fortiter it produces and preserves the divine seed in the heart and watches over its development (Ia, q. 22, a. 4).

3) Although providence, as the divine ordinance, extends immediately to all reality and goodness, to the last and least fiber of every being, nevertheless in the execution of the plan of providence, God governs the lower creation through the higher, to which He thus communicates the dignity of causality (Ia, q. 22, a. 3).

These various characteristics of providence we will now consider as they are presented to us in the Old and New Testaments. No better way can be found to make our knowledge of them not merely abstract and theoretical, but living and spiritually fruitful.

15. The Characteristics Of Providence According To The Old Testament¶

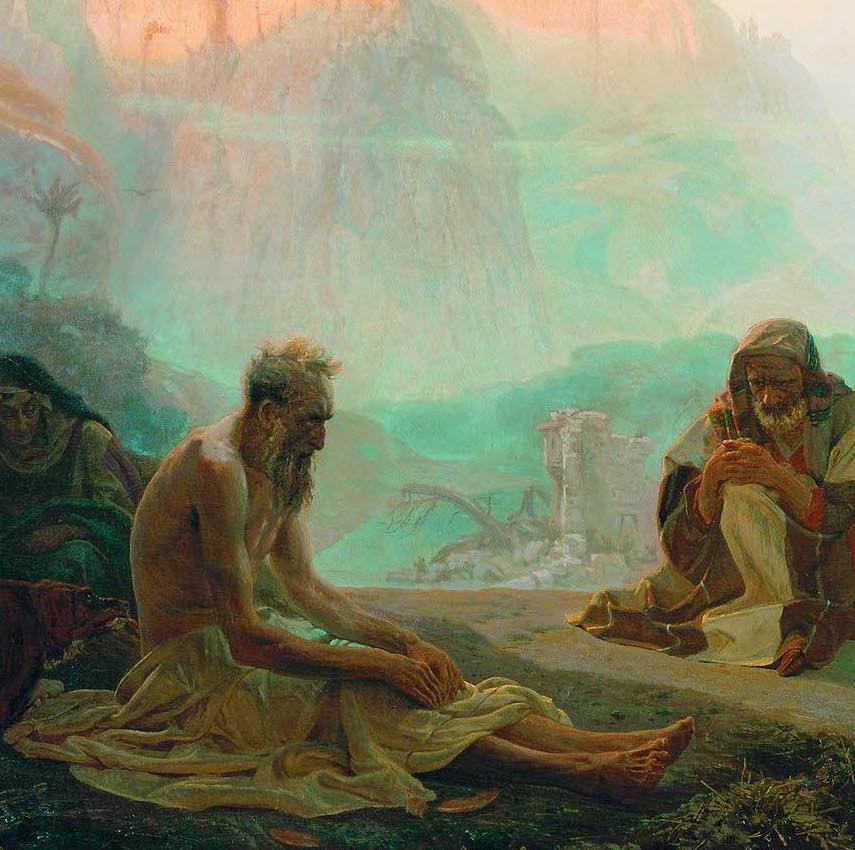

In many passages of the Old Testament (e. g., Wis. 6: 8; 8: I; 11: 21; 12: 13; 17: 2), the doctrine about providence is expressed in terms that are formal and explicit, and implicitly it is indicated in a multitude of other texts. Indeed the Book of Job is devoted entirely to the consideration of providence in relation to the trials the just endure; and wherever we find mention of prayer, we have an equivalent affirmation of providence, for prayer presupposes it.

The Old Testament teaching on this subject may be summed up in these two fundamental points:

1) A universal and infallible providence directs all things to a good purpose.

2) For us providence is an evident fact, sometimes even a startling fact, though in certain of its ways it remains absolutely unfathomable.

We have chosen an abundant array of Scriptural texts, and grouped them in such a way that they explain one another. The words of the texts are more beautiful than any commentary can make them.

A universal and infallible providence directs all things to a good purpose

1) The universality of providence, reaching down to the minutest things, is clearly taught in the Old Testament. The Book of Wisdom declares it repeatedly: “God made the little and the great, and He hath equally care of all” (6: 8) ; “Wisdom reacheth from end to end mightily and ordereth all things sweetly” (8: 1) ; “Thou hast ordered all things in number, measure, and weight” (11: 21) ; “There is no other God but Thou, who hast care of all, that Thou shouldst show that Thou dost not give judgment unjustly” (12: 13). The author then gives this striking example:

Again, another, designing to sail, and beginning to make his voyage through the raging waves…. The wood that carrieth him the desire of gain devised, and the workman built it by his skill. But Thy providence, O Father, governeth it: for Thou hast made a way even in the sea, and a most sure path even among the waves, showing that Thou art able to save out of all things…. Therefore men also trust their lives even to a little wood, and passing over the sea by ship are saved (14: 1-5).

This simple description of the confidence shown by those who sail the seas on a “little wood” proclaims more clearly than all the writings of Plato and Aristotle the existence of a providence extending to the minutest things. We find the same explicit declarations in certain beautiful prayers of the Old Testament: for instance, in Judith’s prayer before she set out for the camp of Holofernes:

Assist, I beseech Thee, O Lord God, me a widow. For Thou hast done the things of old, and hast devised one thing after another: and what Thou hast designed hath been done. For all Thy ways are prepared, and in Thy providence Thou hast placed Thy judgments. Look upon the camp of the Assyrians now, as Thou wast pleased to look upon the camp of the Egyptians… and the waters overwhelmed them. So may it be with these also, O Lord, who trust in their multitude, and in their chariots, and in their pikes, and in their shields, and in their arrows, and glory in their spears: and know not that Thou art our God, who destroyest wars from the beginning. And the Lord is Thy name…. The prayer of the humble and the meek have always pleased Thee. O God of the heavens, Creator of the waters, and Lord of the whole creation, hear me a poor wretch, making supplication to Thee, and presuming of Thy mercy (Judith 9: 3-17).

Here, besides the existence of an all-embracing providence and the rectitude of its ways, there is also brought out the freedom of the divine election regarding the nation from which the Savior was to be born.

But what is the manner of this divine ordinance?

2) The infallibility of providence touching everything that happens, including even our present and future free actions, is stressed in the Old Testament no less clearly than its universal extent. In this connection we must cite especially the prayer of Mardochai (Esther 13: 9-17), in which he implores God’s help against Aman and the enemies of the chosen people:

O Lord, Lord almighty King, for all things are in Thy power, and there is none that can resist Thy will, if Thou determine to save Israel. Thou hast made heaven and earth, and all things that are under the cope of heaven. Thou art the Lord of all, and there is none that can resist Thy majesty. Thou knowest all things, and Thou knowest that it was not out of pride and contempt or any desire of glory that I refused to worship the proud Aman…. But I feared lest I should transfer the honor of my God to a man…. And now, O Lord, O King, O God of Abraham, have mercy on Thy people, because our enemies resolve to destroy us…. Hear my supplication…. And turn our mourning into joy, that we may live and praise Thy name.

Not less touching is Queen Esther’s prayer in those same circumstances (14: 12-19), bringing out even more clearly the infallibility of providence regarding even the free acts of men; for she asks that the heart of King Assuerus be changed, and her prayer is answered: “Remember, O Lord, and show Thyself to us in the time of our tribulation, and give me boldness, O Lord, King of gods, and of all power. Give me a well ordered speech in my mouth in the presence of the lion: and turn his heart to the hatred of our enemy; that both he himself may perish, and the rest that consent to him. But deliver us by Thy hand: and help me who hath no helper, but Thee, O Lord, who hast the knowledge of all things. And Thou knowest that I hate the glory of the wicked…. Deliver us from the hand of the wicked. And deliver me from my fear.” In fact, as we read a little later on (15: 11), “God changed the king’s spirit into mildness; and all in haste and in fear [seeing Esther faint before him], he leaped from his throne and held her in his arms till she came to herself.” Thereupon, after speedily assuring himself of Aman’s treachery, he sent him to his punishment, and leant all the weight of his power to the Jews in defending themselves against their enemies. 34

From this it is plain that divine providence extends infallibly not only to the least external happening but also to the most intimate secrets of the heart and every free action; for, in answer to the prayer of the just, it brings about a change in the interior dispositions of the will of kings. Socrates and Plato never rose to such lofty conceptions, to such firm convictions on this matter of the divine governance.

Many other texts in the Bible to the same effect are repeatedly insisted upon by both St. Augustine and St. Thomas.

In Proverbs, for instance, we read (21: 1) : “As the division of the waters, so the heart of the king is in the hand of the Lord: whithersoever He will He shall turn it. Every way of man seemeth right to himself: but the Lord weigheth the hearts.” Again, in Ecclesiasticus (33: 13) we read: “As the potter’s clay is in his hand, to fashion and order it: all his ways are according to his ordering. So man is in the hand of Him who made Him: and He will render to him according to His judgment.” Again, Isaias in his prophecies against the heathen (14:24) says: “The Lord of hosts hath sworn, saving: Surely as I have thought, so shall it be. And as I have purposed, so shall it fall out: that I will destroy the Assyrian in My land… and his yoke shall be taken away from them.” “This is the hand, ” the prophet adds, “that is stretched out upon all nations. For the Lord of hosts hath decreed, and who can disannul it? And His hand is stretched out, and who shall turn it away?” Always there is the same insistence on the liberty of the divine election, on a universal and infallible providence reaching down to the minutest detail and to the free actions of men.

3) For what end has this universal and infallible providence directed all things? Though the psalms do not bring that full light to bear which comes with the Gospel, they frequently answer this question when they declare that God directs all things to good, for the manifestation of His goodness, His mercy, and His justice, and that He is in no way the cause of sin, but permits it in view of a greater good Providence is thus presented as a divine virtue inseparably united with mercy and justice, just as true prudence in the man of virtue can never be at variance with the moral virtues of justice, fortitude, and moderation which are intimately connected with it. Only in God, however, can this connection of the virtues reach its supreme perfection.

Again and again we find in the psalms such expressions as these: “All the ways of the Lord are mercy and truth” (24:10) ; “All His works are done with faithfulness. He loveth mercy and judgment [Heb., justice and right] ; the earth is full of the mercy of the Lord” (32: 4-5) ; “Show, O Lord, Thy ways to me, and teach me Thy paths. Direct me in Thy truth, and teach me; for Thou art God my Savior, and on Thee I have waited all the day long. Remember, O Lord, Thy bowels of compassion; and Thy mercies that are from the beginning of the world. The sins of my youth and my ignorances do not remember. According to Thy mercy remember me: for Thy goodness’ sake, O Lord” (24: 4-7).” The Lord ruleth me: and I shall want nothing. He hath set me in a place of pasture. He hath brought me up on the water of refreshment: He hath converted my soul. He hath led me on the paths of justice, for His name’s sake. For though I should walk in the midst of the shadow of death, I will fear no evils, for Thou art with me. Thy rod and Thy staff: they have comforted me” (22: 1-5).” In Thee, O Lord, have I hoped, let me never be confounded…. My lots are in Thy hands. Deliver me out of the hands of my enemies, and from them that persecute me. Make Thy face to shine on Thy servant: save me in Thy mercy…. O how great is the multitude of Thy sweetness, O Lord, which Thou has hidden from them that fear Thee! Which Thou has wrought for them that hope in Thee, in the sight of the sons of men. Thou shalt hide them in the secret of Thy face from the disturbance of men. Thou shalt protect them in Thy tabernacle from the contradiction of tongues” (30: I, 16, 17, 20).

Here we have the twofold foundation of our hope and trust in God: His providence, with its individual care for each one of the just, and His omnipotence. All these passages in the psalms may be summed up in St. Teresa’s words already quoted: “Lord, Thou knowest all things, canst do all things, and Thou lovest me.”

Since providence is of such absolute universality, extending to the minutest details, and since at the same time it is infallible and directs all things to good, surely it ought to be quite evident to those who are willing to see it. How, then, in its ways is it so often impenetrable even to the just? The Old Testament more than once touches on this great problem.

Providence is for us an evident fact, yet in certain of its ways it remains absolutely unfathomable

According to the Bible, the evidence that providence in general exists, is obtained either from the order apparent in the world or from the history of the chosen people or again from the main features of the lives of the just and of the wicked.

The order apparent in the world, declare the psalms, proclaims the existence of an intelligent designer: “The heavens show forth the glory of God: and the firmament declareth the work of His hands” (18: 2) ; “Sing ye to the Lord with praise: sing to our God upon the harp; who covereth the heavens with clouds, and prepareth rain for the earth; who maketh grass to grow on the mountains, and herbs for the service of men, who giveth to beasts their food, and to the young ravens that call upon Him” (146: 7; cf. Job 38: 41) ; “All men are vain, in whom there is not the knowledge of God: and who by these good things that are seen could not understand Him that He is. Neither by attending to the works have acknowledged who was the workman…. They are not to be pardoned. For if they were able to know so much as to make a judgment of the world, how did not they more easily find out the Lord thereof?” (Wis. 13: I, 4, 8.)

Providence is no less clearly seen in the history of the chosen people, as the psalms again remind us, especially PS. 113, In exitu Israel de Aegypto:

When Israel went out of Egypt… the sea saw and fled: Jordan was turned back…. What ailed thee, O thou sea, that thou didst flee? and thou, O Jordan, that thou wast turned back? Ye mountains that skipped like rams, and ye hills like lambs of the flock? At the presence of the God of Jacob: who turned the rock into pools of water, and the stony hill into fountains of waters. Not to us, O Lord, not to us: but to Thy name give glory. For Thy mercy and for Thy truth’s sake…. The Lord hath been mindful of us and hath blessed us. He hath blessed the house of Israel…. He hath blessed all that fear the Lord, both little and great…. But we that live bless the Lord: from this time now and forever.

Lastly, providence is clearly shown in the general life of the just, in the often perceptible happiness with which it rewards them. As we read in psalm 111:

Blessed is the man that feareth the Lord: he shall delight exceedingly in His commandments. His seed shall be mighty on the earth: the generation of the righteous shall be blessed. Glory and wealth shall be in his house: and his justice remaineth forever and ever. To the righteous a light hath risen up in darkness: He is merciful, compassionate and just…. His heart is ready to hope in the Lord, his heart is strengthened: he shall not be moved until he look over his enemies. He hath given to the poor: His justice remaineth forever and ever.

The providence of God is especially to be seen in the case of those in tribulation, “raising up the needy from the earth and lifting up the poor out of the dunghill. That He may place him with the princes of His people” (Ps. 112: 7).

On the other hand, the malice of the wicked receives its chastisement even in this world, often in a most striking way, another sign of the divine governance: “Be not delighted in the paths of the wicked…. Flee from it, pass not by it…. They eat the bread of wickedness…. But the path of the just, as a shining light, goeth forward and increaseth even to a perfect day. The way of the wicked is darksome: they know not where they fall” (Prov., chap. 4). 35 God withdraws His blessing from the wicked and delivers them up to their own blindness; but to His servants He lends His aid, sometimes in marvelous ways, as when He said to Elias (III Kings 17: 3) : “Get thee hence and go towards the east and hide thyself by the torrent Carith…. I have commanded the ravens to feed thee there.” In obedience to the word of the Lord he departed and took up his abode by the torrent of Carith; and the ravens brought him bread and meat in the morning and eventide, and he drank water from the torrent.

Although providence is thus evident in the life of the just taken as a whole, nevertheless in some of its ways it remains inscrutable. Especially is this so in its more advanced stages, where the obscurity is due solely to an overpowering radiance dazzling our feeble sight. An outstanding example is that passage from Isaias which predicts the sufferings of the Servant of Yahweh, or the Savior.

Again in psalm 33: 20, we read: “Many are the tribulations of the just; but out of them all will the Lord deliver them.” Judith says:

Our fathers were tempted that they might be proved, whether they worshiped their God truly…. Abraham was tempted and, being proved by many tribulations, was made the friend of God. So Isaac, so Jacob, so Moses, and all that have pleased God, have passed through many tribulations, remaining faithful…. Let us not revenge ourselves for these things which we suffer. But esteeming these very punishments to be less than our sins deserve, let us believe that these scourges of the Lord, with which like servants we are chastised, have happened for our amendment, and not for our destruction (Judith 8: 21-27).

The prophets often spoke of the mysterious character of certain ways of providence, especially when, like Jeremias, they realized the comparative futility of their efforts. Isaias (55:6) writes:

Seek ye the Lord while He may be found: call upon Him while He is near. Let the wicked forsake his way and the unjust man his thoughts, and let him return to the Lord; and He will have mercy on him: and to our God; for He is bountiful to forgive. For my thoughts are not your thoughts: nor your ways my ways, saith the Lord. For as the heavens are exalted above the earth, so are my ways exalted above your ways, and my thoughts above your thoughts.

We find the same expressed in psalm 35: 7: “Thy justice, O Lord, is as the mountains of God: Thy judgments are a great deep.”

Nevertheless, in this higher darkness, so different from the lower darkness of sin and death, the just man discovers which way his true path lies: he learns to distinguish more and more clearly these two kinds of darkness, which are at opposite extremes. 36 Let us say with the just Tobias (13: 1) after the trials he had endured:

Thou art great, O Lord, forever, and Thy kingdom is unto all ages. For Thou scourgest and Thou savest: Thou leadest down to hell, and bringest up again: and there is none that can escape Thy hand. Give glory to the Lord, ye children of Israel: and praise Him in the sight of the Gentiles. Because He has therefore scattered you among the Gentiles, who know not Him, that you may declare His wonderful works: and make them know that there is no other almighty God besides Him. He hath chastised us for our iniquities: and He will save us for His own mercy. 37 Be converted, therefore, ye sinners: and do justice before God, believing that He will show His mercy to you.

These, then, are the principal statements in the Old Testament concerning providence. It is universal, extending to the minutest detail, to the secrets of the heart. It is infallible, regarding everything that happens, even our free actions. It directs all things to good, and at the prayer of the just will change the heart of the sinner. For those who will but see, it is an evident fact, yet in certain of its ways it remains inscrutable. This teaching shows us what confidence we should have in God and with what wholehearted abandonment we should surrender ourselves to Him in times of trial by perfect conformity to His divine will; then will He direct all things to our sanctification and salvation. And so the Gospel proclaims: “Seek ye first the kingdom of God and His justice: and all these things shall be added unto you” (Luke 12: 31).

17. Providence According To The Gospel¶

The existence of providence, its absolute universality extending to the smallest detail, and its infallibility regarding everything that comes to pass, not excepting our future free actions—all this the New Testament again brings out, even more clearly than the Old. Much more explicit, too, than in the Old Testament is the conception given us here of that higher good to which all things have been directed by providence, though in certain of its more advanced ways it still remains unfathomable. These fundamental points we shall examine one by one, giving prominence to the Gospel texts that most clearly express them.

The higher good to which all things are directed by providence

Our Lord in the Gospels raises our minds to the contemplation of the divine governance by directing our attention to the admirable order prevailing in the things of sense, and giving us some idea of how much more so this order of providence is to be found in spiritual things, an order more sublime, more bountiful, more salutary, and imperishable. We have seen that a similar order is to be found, though less clearly, in God’s answer at the end of the Book of Job; if there are such extraordinary marvels to be met with in the world of sense, what wonderful order ought we not to expect in the spiritual world.

In the Gospel of St. Matthew we read (6: 25-34) :

Be not solicitous for your life, what you shall eat, nor for your body, what you shall put on. Is not the life more than the meat and the body more than the raiment? Behold the birds of the air, for they neither sow, nor do they reap nor gather into barns: and your heavenly Father feedeth them. Are not you of more value than they? And which of you by taking thought can add to his stature one cubit? And for your raiment why are you solicitous? Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow: they labor not, neither do they spin. But I say to you that not even Solomon in all his glory was arrayed as one of these. And if the grass of the field, which is today and tomorrow is cast into the oven, God doth so clothe: how much more you, O ye of little faith? Be not solicitous therefore, saying: What shall we eat: or, what shall we drink: or, wherewith shall we be clothed? For after all these things do the heathens seek. For your heavenly Father knoweth that you have need of all these things. Seek ye therefore first the kingdom of God and His justice: and all these things shall be added unto you. Be not therefore solicitous for tomorrow: for the morrow will be solicitous for itself. Sufficient for the day is the evil thereof.

These examples serve to show that providence extends to all things, and gives to all beings what is suitable to their nature. God provides the birds of the air with their food and also has endowed them with instinct which directs them to seek out what is necessary and no more. If this is His way of dealing with the lower creation, surely He will have a care for us.

If providence provides what is needful for the birds of the air, how much more attentive will it be to the needs of such as we, who have a spiritual, immortal soul, with a destiny incomparably more sublime than that of the animal creation. The heavenly Father knows what we stand in need of. What, then, must our attitude be? First of all we must seek the kingdom of God and His justice, and then whatever is necessary for our bodily subsistence will be given us over and above. Those who make it their principal aim to pursue their final destiny (God the sovereign good who should be loved above all things), will be given whatever is necessary to attain that end, not only what is necessary for the life of the body, but also the graces to obtain life eternal. 47

Our Lord refers to providence again in St. Matthew (10: 28) : “Fear ye not them that kill the body and are not able to kill the soul: but rather fear him that can destroy both soul and body in hell. Are not two sparrows sold for a farthing? And not one of them shall fall to the ground with. out your Father. But the very hairs of your head are all numbered. Fear not therefore: better are you than many; sparrows.” So again in St. Luke (12: 6-7).

Always it is the same a fortiori argument from the care the Lord has for the lower creation and thence leading us to form some idea of what the divine governance must be in the order of spiritual things.

As St. Thomas points out in his commentary on St. Matthew, what our Lord wishes to convey is this: It is not the persecutor we should fear; he can do no more than hurt our bodies, and what little harm he is capable of he cannot actually inflict without the permission of providence, which only allows these evils to befall us in view of a greater good. If it is true that not a single sparrow falls to the ground without our heavenly Father’s permission, surely we shall not fall without His permission, no, nor one single hair of our head. This is equivalent to saying that providence extends to the smallest detail, to the least of our actions, every one of which may and indeed must be directed to our final end.

Besides the universality of providence, the New Testament brings out in terms no less clear its infallibility regarding everything that comes to pass. It is pointed out in the text just mentioned: “The very hairs of your head are all numbered.” This infallibility extends even to the secrets of the heart and to our future free actions. In St. John (6: 64) we read: “The words that I have spoken to you are spirit and life. But there are some of you that believe not”; and the Evangelist adds: “For Jesus knew from the beginning who they were that did not believe and who he was that would betray Him.” Again (13: 11) during the last supper Jesus told those who were present: “You are clean, but not all”; for, continues St. John, “He knew who he was who would betray Him; and therefore He said: You are not all clean.” St. Matthew also records the words, “One of you is about to betray me.” Now if Jesus thus has certain knowledge of the secrets of hearts and, as His prediction of persecutions shows, of future free actions, they must surely be infallibly known to the eternal Father.

In St. Matthew (6: 4-6), we are told: “When thou shalt pray, enter into thy chamber and, having shut the door, pray to thy Father in secret: and thy Father who seeth in secret will repay thee.” And later we find St. Paul saying to the Hebrews (4:13) : “Neither is there any creature invisible in His sight: but all things are naked and open to His eyes, to whom our speech is.”

The teaching on the necessity of prayer, to which the Gospel is constantly returning, obviously presupposes a providence extending to the very least of our actions. In St. Matthew (7: 7-11) our Lord tells us: “If you then being evil, know how to give good things to your children: how much more will your heavenly Father who is in heaven give good things to them that ask Him?” Here is another and stronger argument for divine providence based on the attentive care shown by a human father for his children. If he watches over them, much more will our heavenly Father watch over us.

Likewise, the parable of the wicked judge and the widow in St. Luke (18: I-8) is an incentive to us to pray with perseverance. Annoyed by the persistent entreaties of the widow, the judge finally yields to her just demands so that she may cease to be troublesome to him.” And the Lord said: Hear what the unjust judge saith. And will not God revenge his elect who cry to him day and night: and will he have patience in their regard?”

Our Lord proclaims the same truth in St. John (10:27) : “My sheep hear My voice. And I know them: and they follow Me. And I give them life everlasting: and they shall not perish forever. And no man shall pluck them out of My hand. That which My Father hath given Me is greater than all: and no one can snatch them out of the hand of My Father. I and the Father are one.” These words point out emphatically the infallibility of providence concerning everything that comes to pass, including even our future free actions.

But what the Gospel message declares even more clearly is whether there is not after all some higher, some eternal purpose to which the divine governance directs all things, and further, that if it permits evil and sin—it cannot in any way be its cause—it does so only in view of some greater good.

In St. Matthew we read (5: 44) : “Love your enemies: do good to them that hate you: and pray for them that persecute and calumniate you: that you may be the children of your Father who is in heaven, who maketh His sun to rise upon the good and bad and raineth upon the just and the unjust.” And again in St. Luke (6: 36) : “Be ye therefore merciful, as your heavenly Father is merciful.” Persecution itself is turned to the good of those who endure it for the love of God: “Blessed are they that suffer persecution for justice’ sake: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are ye when they shall revile you and persecute you and speak all that is evil against you, untruly, for My name’s sake: be glad and rejoice, for your reward is very great in heaven. For so they persecuted the prophets that were before you” (Matt. 5: 10).

Here is the full light heralded from afar in the Book of Job and more distinctly in this passage from the Book of Wisdom (3: I-8) : “The souls of the just are in the hand of God… in time they shall shine… they shall judge nations: and their Lord shall reign forever.”

Here is the full light of which we were given a glimpse in the Book of Machabees (11: 7-9), where, as we have seen, one of the martyrs, on the point of expiring, thus addresses his persecutor: “Thou, O most wicked man, destroyest us out of this present life: but the King of the world will raise us up, who die for His laws, in the resurrection of eternal life.”

In the light of this revealed teaching, St. Paul writes to the Romans (5: 3) : “We glory also in tribulations, knowing that tribulation worketh patience: and patience trial; and trial hope; and hope confoundeth not; because the charity of God is poured forth in our hearts, by the Holy Ghost who is given to us.” And again (8: 28) : “We know that to them that love God all things work unto good: to such as according to His purpose are called to be saints.” This last text sums up all the rest, revealing how this universal and infallible providence directs all things to a good purpose, not excluding evil, which it permits without in any way causing it. And now there remains the question as to the sort of knowledge we can have of the plan pursued by the divine governance.

The light and shade in the providential plan

We have found clearly expressed in the Old Testament the truth that for us divine providence is an evident fact, yet that certain of its ways are unfathomable. This truth is brought out in still greater relief in the New Testament in connection with sanctification and eternal life.

Providence is an evident fact from the order prevailing in the universe, from the general working of the Church’s life, and again from the life of the just taken as a whole. This is affirmed in the words of our Lord just quoted: “Behold the birds of the air, for they neither sow, nor do they reap, nor gather into barns: and your heavenly Father feedeth them. Are not you of much more value than they?” (Matt. 6: 26.) So again St. Paul (Rom. 1: 20) : “The invisible things of Him from the creation of the world are clearly seen, being understood by the things that are made, His eternal power and divinity.”

In the parables of the prodigal son, the lost sheep, the good shepherd, and the talents, our Lord also illustrates how providence is concerned with the souls of men. All that tenderness of heart shown by the father of the prodigal is already in an infinitely more perfect way possessed by God, whose providence watches over the souls of men more than any other earthly creature, in the lives of the just especially, in which everything is made to concur in their final end.

Jesus also proclaims how with His Father He will watch over the Church, and we now find verified these words of His: “Thou art Peter, and upon this rock I will build My Church. And the gates of hell shall not prevail against it” (Matt. 16: 18) ; “Going therefore, teach ye all nations: baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost; teaching them to observe all things whatsoever I have commanded you. And behold I am with you all days, even to the consummation of the world” (Matt. 28: 1920). We are now witnessing in the spread of the Gospel in the nations throughout the five continents the realization of this providential plan, which in its general lines stands out quite distinctly.

In this plan of providence, however, there are also elements of profound mystery, and our Lord will have us to understand that to the humble and childlike, however, these mysterious elements will appear quite simple; their humility will enable them to penetrate even to the heights of God. First and foremost there is the mystery of the redemption, of the sorrowful passion and all that followed, a mystery which Jesus only reveals to His disciples little by little as they are able to bear it, a mystery that at the moment of its accomplishment will be a cause of confusion to them.

There is also the whole mystery of salvation: “I confess to Thee, O Father, Lord of heaven and earth, because Thou hast hidden these things from the wise and prudent and hast revealed them to little ones. Yea, Father: for so hath it seemed good in Thy sight” (Matt. 11: 25) ; “My sheep hear my voice. And I know them: and they follow me. And I give them life everlasting: and they shall not perish forever” (John 10: 27).

“There shall arise false christs and false prophets and shall show great signs and wonders, insomuch as to deceive (if possible) even the elect” (Matt. 24:24) ; “Of that day and hour [the last] no one knoweth: no, not the angels in heaven, but the Father alone. [And the same must be said of the hour of our death.] Watch ye therefore, because you know not what hour your Lord will come” (Matt. 24: 36, 42). The Apocalypse, which foretells these events in obscure and symbolic language, remains still a book sealed with seven seals (Apoc. 5: 1).

Later on St. Paul lays stress on these mysterious ways of Providence.” The foolish things of the world hath God chosen, that He may confound the wise: and the weak things of the world and the things that are contemptible, hath God chosen, and things that are not, that He might bring to nought the things that are; that no flesh should glory in His sight” (I Cor. 1: 27). It was through the Apostles, some of whom were chosen from the poor fisherfolk of Galilee, that Jesus triumphed over paganism and converted the world to the Gospel, at the very moment when Israel in great part proved itself unfaithful. God can choose whomsoever He will without injustice to anyone.

Freely He made choice in former times of the people of Israel, one among the various nations; from the sons of Adam He chose Seth in preference to Cain, then Noe and afterwards Sem He preferred to his brothers, then Abraham; He preferred Isaac to Ismael, and last of all Jacob. And now, freely He calls the Gentiles and permits Israel in great part to fall away. Here is one of the most striking examples of the light and shade in the plan of providence; 48 it may be summed up in this way. On the one hand God never commands the impossible, but, to use St. Paul’s words, will have all men to be saved (I Tim. 2: 4). On the other hand, as St. Paul says again, “What hast thou that thou hast not received?” (I Cor. 4: 7.) One person would not be better than another, were he not loved by God more than the other, since His love for us is the source of all our good. 49 These two truths are as luminous and certain when considered apart as their intimate reconciliation is obscure, for it is no less than the intimate reconciliation of infinite justice, infinite mercy, and supreme liberty. They are reconciled in the Deity, the intimate life of God; but for us this is an inaccessible mystery, as white light would be to someone who had never perceived it, but had seen only the seven colors of the rainbow.

This profound mystery prompts St. Paul’s words to the Romans (11: 25-34) :

Blindness in part has happened in Israel, until the fullness of the Gentiles shall come in…. But as touching the election, they [the children of Israel] are most dear for the sake of their fathers… that they also may obtain mercy…. O the depths of the riches of the wisdom and of the knowledge of God! How incomprehensible are His judgments, and how unsearchable His ways! For who hath known the mind of the Lord? Or who hath been His counsellor?… Of Him, and by Him, and in Him, are all things: to Him be glory forever.

But the only reason why these unfathomable ways of providence are obscure to us is that they are too luminous for the feeble eyes of our minds. Simple and humble souls easily recognize that, for all their obscurity and austerity, these exalted ways are ways of goodness and love. St. Paul points this out when he writes to the Ephesians (3: 18) : “I bow my knees to the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, of whom all paternity in heaven and earth is named… that you may be able to comprehend, with all the saints, what is the breadth and length and height and depth, to know also the charity of Christ, which surpasseth all knowledge: that you may be filled unto all the fullness of God.”

Amplitude in the ways of providence consists in their reaching to every part of the universe, to all the souls of men, to every secret of the heart. In their length they extend through every period of time, from the creation down to the end of time and on to the eternal life of the elect. Their depth lies in the permission of evil, sometimes terrible evil, and in view of some higher purpose which will be seen clearly only in heaven. Their height is measured by the sublimity of God’s glory and the glory of the elect, the splendor of God’s reign finally and completely established in the souls of men.

Thus providence is made manifest in the general outlines of the plan it pursues, but its more exalted ways remain for us a mystery. Nevertheless, little by little “to the righteous a light rises in the darkness” (Ps. 111: 4). Every day we can get a clearer insight into these words of Isaias (9: 2) : “The people that walked in darkness have seen a great light: to them that dwelt in the region of the shadow of death, light is risen.” And gradually, if we are faithful, we learn more and more each day to abandon ourselves to that divine providence. which, as the canticle Benedictus says, “directs our steps into the way of peace” (Luke 1: 79).

Abandonment to the divine will is thus one of the fairest expressions of hope combined with charity or love of God. Indeed, it involves the exercise to an eminent degree of all the theological virtues, because perfect self-abandonment to providence is pervaded by a deep spirit of faith, of confidence, and love for God. And when this self-abandonment, far from inducing us to fold our arms and do nothing as is the case with the Quietists, is accompanied by a humble, generous fulfilment of our daily duties, it is one of the surest ways of arriving at union with God and of preserving it unbroken even in the severest trials. Once we have done our utmost to accomplish the will of God day after day, we can and we must abandon ourselves to Him in all else. In this way we shall find peace even in tribulation. We shall see how God takes upon Himself the guidance of souls that, while continuing to perform their daily duties, abandon themselves completely to Him; and the more He seems to blind their eyes, the saints tell us, the more surely does He lead them, urging them on in their upward course into a land where, as St. John of the Cross says, the beaten track has disappeared, where the Holy Ghost alone can direct them by His divine inspirations.

18. Providence And Prayer¶

When we reflect on the infallibility of God’s foreknowledge and the unchangeableness of the decrees of providence, not infrequently a difficulty occurs to the mind. If this infallible providence embraces in its universality every period of time and has foreseen all things, what can be the use of prayer? How is it possible for us to enlighten God by our petitions, to make Him alter His designs, who has said: “I am the Lord and I change not”? (Mal. 3: 6.) Must we conclude that prayer is of no avail, that it comes too late, that whether we pray or not, what is to be will be?

On the contrary, the Gospel tells us: “Ask, and it shall be given you” (Matt. 7: 7). A commonplace with unbelievers and especially with the deists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, this objection in reality arises from an erroneous view as to the primary source of efficacy in prayer and the purpose for which it is intended. The solution of the objection will show the intimate connection between prayer and providence, since (1) it is founded upon providence, (2) it is a practical recognition of providence, and (3) it co-operates in the workings of providence.

Providence, the primary cause of efficacy in prayer

We sometimes speak as though prayer were a force having the primary cause of its efficacy in ourselves, seeking by way of persuasion to bend God’s will to our own; and forthwith the mind is confronted with the difficulty just mentioned, that no one can enlighten God or prevail upon Him to alter His designs.

As clearly shown by St. Augustine and St. Thomas (IIa IIae, q. 83, a. 2), the truth is that prayer is not a force having its primary source in ourselves; it is not an effort of the human soul to bring violence to bear upon God and compel Him to alter the dispositions of His providence. If we do occasionally make use of these expressions, it is by way of metaphor, just a human way of expressing ourselves. In reality, the will of God is absolutely unchangeable, as unchangeable as it is merciful; yet in this very unchangeableness the efficacy of prayer, rightly said, has its source, even as the source of a stream is to be found on the topmost heights of the mountains.

In point of fact, before ever we ourselves decided to have recourse to prayer, it was willed by God. From all eternity God willed it to be one of the most fruitful factors in our spiritual life, a means of obtaining the graces necessary to reach the goal of our life’s journey. To conceive of God as not foreseeing and intending from all eternity the prayers we address to Him in time is just as childish as the notion of a God subjecting His will to ours and so altering His designs.

Prayer is not our invention. Those first members of our race, who, like Abel, addressed their supplications to Him, were inspired to do so by God Himself. It was He who caused it to spring from the hearts of patriarchs and prophets; it is He who continues to inspire it in souls that engage in prayer. He it is who through His Son bids us, “Ask, and it shall be given you: seek and you shall find: knock, and it shall be opened unto you” (Matt. 7: 7).

The answer to the objection we have mentioned is in the main quite simple in spite of the mystery of grace it involves. True prayer, prayer offered with the requisite conditions, is infallibly efficacious because God has decreed that it shall be so, and God cannot revoke what He has once decreed.

It is not only what comes to pass that has been foreseen and intended (or at any rate permitted) by a providential decree, but the manner also in which it comes to pass, the causes that bring about the event, the means by which the end is attained.

Providence, for instance, has determined from all eternity that there shall be no harvest without the sowing of seed, no family life without certain virtues, no social life without authority and obedience, no knowledge without mental effort, no interior life without prayer, no redemption without a Redeemer, no salvation without the application of His merits and, in the adult, a sincere desire to obtain that salvation.

In every order, from the lowest to the highest, God has had in view the production of certain effects and has prepared the necessary causes; with certain ends in view He has prepared the means adequate to attain them. For the material harvest He has prepared a material seed, and for the spiritual harvest a spiritual seed, among which must be included prayer.

Prayer, in the spiritual order, is as much a cause destined from all eternity by providence to produce a certain effect, the attainment of the gifts of God necessary for salvation, as heat and electricity in the physical order are causes that from all eternity are destined to produce the effects of our everyday experience.

Hence, far from being opposed to the efficacy of prayer, the unchangeableness of God is the ultimate guaranty of that efficacy. But more than this, prayer must be the act by which we continually acknowledge that we are subject to the divine governance.

Prayer, an act of worship paid to Providence

The lives of all creatures are but a gift of God, yet only men and angels can be aware of the fact. Plants and animals receive without knowing that they are receiving. It is the heavenly Father, the Gospel tells us, who feeds the birds of the air, but they are unaware of it. Man, too, lives by the gifts of God and is able to recognize the fact. If the sensual lose sight of it, that is because in them reason is smothered by passion. If the proud refuse to acknowledge it, the reason is that they are spiritually blinded by pride causing them to judge all things not from the highest of motives but from what is often sheer mediocrity and paltriness.

If we are of sound mind, we are bound to acknowledge with St. Paul that we possess nothing but what we have received: “What hast thou that thou hast not received?” (I Cor. 4:7.) Existence, health and strength, the light of intelligence, any sustained moral energy we may have, success in our undertakings, where the least trifle might mean failure —all these are the gifts of Providence. And, transcending reason, faith tells us that the grace necessary for salvation and still more the Holy Ghost whom our Lord promised are pre-eminently the gift of God, the gift that Jesus refers to in these words of His to the Samaritan woman, “If thou didst know the gift of God” (John 4: 10).

Thus when we ask of God in the spirit of faith to give health to the sick, to enlighten our minds so that we may see our way clearly in difficulties, to give us His grace to resist temptation and persevere in doing good, this prayer of ours is an act of worship paid to Providence.

Mark how our Lord invites us to render this daily homage to Providence, morning and evening, and frequently in the course of the day. Recall to mind how He, after bidding us, “Ask and it shall be given you” (Matt. 7: 7), goes on to bring out the goodness of Providence in our regard: “What man is there among you, of whom if his son shall ask bread, will he reach him a stone? Or if he shall ask him a fish, will he reach him a serpent? If you then being evil, know how to give good gifts to your children: how much more will your Father who is in heaven give good things to them that ask Him?” (Matt. 7: 7, 9-11.) Our Lord’s statement carries its own proof. If there is any kindness in a father’s heart, does it not come to him from the heart of God or from His love?

Sometimes indeed God might be said to reverse the parts, when through His prevenient actual graces He urges us to pray, to render due homage to His providence and obtain from it what we stand most in need of. Recall, for instance, how our Lord led on the Samaritan woman to pray: “If thou didst know the gift of God and who He is that saith to thee: Give me to drink: thou perhaps wouldst have asked of Him, and He would have given thee living water… springing up into life everlasting” (John 4: 10, 14). The Lord entreats us to come to Him; He waits for us patiently, always eager to listen to us.

The Lord is like a father who has already decided to grant some favor to His children, yet prompts them to ask it of Him. Jesus first willed that the Samaritan woman should be converted and then gradually caused her to burst forth in heartfelt prayer; for sanctifying grace is not like a liquid that is poured into an inert vessel; it is a new life, which the adult will receive only if he desires it.

Sometimes God seems to turn a deaf ear to our prayer, especially when it is not sufficiently free from self-interest, seeking temporal blessings for their own sake rather than as useful for salvation. Then gradually grace invites us to pray better, reminding us of the Gospel words: “Seek ye first the kingdom of God and His justice: and all these things shall be added unto you” (Matt. 6: 33).

Indeed at times it seems that God repulses us as if to see whether we shall persevere in our prayer. He did so to the Canaanite woman. The harshness of His words to her seemed like a refusal: “I was not sent but to the sheep that are lost of the house of Israel… It is not good to take the bread of the children and to cast it to the dogs.” Inspired undoubtedly by grace that came to her from Christ, the woman replied: “Yea, Lord: for the whelps also eat of the crumbs that fall from the table of their masters.” “O woman, ” Jesus said, “great is thy faith. Be it done to thee as thou wilt” (Matt. 15: 23, 26-28). And her daughter was delivered from the demon that was tormenting her.

When we really pray, it is an acknowledgment, a practical and not merely abstract or theoretical acknowledgment, that we are under the divine governance, which infinitely transcends the governance of men. Whether our prayer takes the form of adoration or supplication or thanksgiving or reparation, it should thus unceasingly render to providence that homage which is its due.

Prayer co-operates in the divine governance

Prayer is not in opposition to the designs of Providence and does not seek to alter them, but actually co-operates in the divine governance, for when we pray we begin to wish in time what God wills for us from all eternity.

When we pray, it may seem that the divine will submits to our own, whereas in reality it is our will that is uplifted and made to harmonize with the divine will. All prayer, so the Fathers say, is an uplifting of the soul to God, whether it; be prayer of petition, of adoration, of praise, or of thanksgiving, or the prayer of reparation which makes honorable amends.

One who prays properly, with humility, confidence, and perseverance, asking for the things necessary for salvation, does undoubtedly co-operate in the divine governance. In stead of one, there are now two who desire these things. It is God of course who converted the sinner for whom we have so long been praying; nevertheless we have been God’s partners in the conversion. It is God who gave to the soul in tribulation that light and strength for which we have so long besought Him; yet from all eternity He decided to produce this salutary effect only with our co-operation and as the result of our intercession.

The consequences of this principle are numerous. First, the more prayer is in conformity with the divine intentions, the more closely does it co-operate in the divine governance. That there may be ever more of this conformity in our prayer, let us every day say the Our Father slowly and with great attention; let us meditate upon it, with love accompanying our faith. This loving meditation will become contemplation, which will ensure for us the hallowing and glorifying of God’s name both in ourselves and in those about us, the coming of His kingdom and the fulfilment of His will here on earth as in heaven. It will obtain for us also the forgiveness of our sins and deliverance from evil, as well as our sanctification and salvation.

From this it follows that our prayer will be the purer and more efficacious when we pray in Christ’s name and offer to God, in compensation for the imperfections of our own love and adoration, those acts of love and adoration that spring from His holy soul.

A Christian who says the Our Father day by day with gradually increasing fervor, who says it from the bottom of his heart, for others as well as for himself, undoubtedly cooperates very much in the divine governance. He co-operates far more than the scientists who have discovered the laws governing the stars in their courses or the great physicians who have found cures for some terrible diseases. The prayer of St. Francis, St. Dominic, or, to come nearer to our own times, St. Teresa of the Child Jesus, had an influence certainly not less powerful than that of a Newton or a Pasteur. One who really prays as the saints have prayed, co-operates in the saving not only of bodies but of souls. Every soul, through its higher faculties, opens upon the infinite, and is, as it were, a universe gravitating toward God.

Close attention to these intimate relations between prayer and providence will show that prayer is undoubtedly a more potent force than either wealth or science. No doubt science accomplishes marvelous things; but it is acquired by human means, and its effects are confined within human limits. Prayer, indeed, is a supernatural energy with an efficacy coming from God and the infinite merits of Christ, and from actual grace that leads us on to pray. It is a spiritual energy more potent than all the forces of nature together. It can obtain for us what God alone can bestow, the grace of contrition and of perfect charity, the grace also of eternal life, the very end and purpose of the divine governance, the final manifestation of its goodness.

At a time when so many perils threaten the whole world, we need more to reflect on the necessity and sublimity of true prayer, especially when it is united with the prayer of our Lord and of our Lady. The present widespread disorder must by contrast stimulate us constantly to reflect that we are subject not only to the often unreasoning, imprudent government of men, but also to God’s infinitely wise governance. God never permits evil except in view of some greater good. He wills that we co-operate in this good by a prayer that becomes daily more sincere, more humble, more profound, more confident, more persevering, by a prayer united with action, in order that each succeeding day shall see more perfectly realized in us and in those about us that petition of the Our Father: “Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven.” At a time when Bolshevism is putting forth every effort against God, it behooves us to repeat it again and again with ever deepening sincerity, in action as well as in word, so that as time goes on God’s reign may supersede the reign of greed and pride. Thus in a concrete, practical way we shall at once see that God permits these present evils only because He has some higher purpose in view, which it will be granted us to see, if not in this world. at any rate after our death

- 29

See Part I. chap. 2: “On the order in the world.”

- 30

Cf. St. Thomas, Ia, q. 79, a. 1, 2.

- 31

Physical evils, sickness, for instance, are not willed by God directly, but only in an accidental way, insomuch as He wills a higher good of which physical evil is the necessary condition. Thus the lion depends for its existence on the killing of the gazelle, patience in sickness presupposes pain, the heroism of the saints presupposes the sufferings they endure. (Cf. St. Thomas, Ia, q. 19, a. g; q. 22, a. 2 ad 2um.)

- 32

Cf. St. Thomas, Ia, q. 83, a. 1 ad 3um: “God, by moving voluntary causes, does not deprive their actions of being voluntary, but rather is He the cause of this very thing in them.” Cf. also, Ia, q. 103, a. 5-8; q. 105, a. 4, 5; q. 106, a. 2; Ia IIae, q. 10, a. 4 ad Ium et ad 3um; q. 109, a. 1, etc.

- 33

The free mode in our choice consists in the indifference that dominates our will in its actual process of tending to a particular object presented as good under one aspect and not good under another, and consequently as unable to exert an invincible attraction upon it (Ia IIae, q. 10, a. 2). This free mode in our choice is still within the sphere of being, of reality, and as such comes under the adequate object of the divine omnipotence. On the contrary, this cannot be so with the disorder of sin. God, in His causation infallible, can no more be the cause of sin than the eye can perceive sound (Ia IIae, q. 79, a. 1, 2).

- 34

Cf. also Daniel 13: 42: The prayer of Susanna.

- 35

Ps. 36: 10-15: “Yet a little while, and the wicked shall not be: and thou shalt seek his place, and shalt not find it. But the meek shall inherit the land: and shall delight in abundance of peace. The sinner shall watch the just man: and shall gnash upon him his teeth. But the Lord shall laugh at him: for He foreseeth that His day shall come. The wicked have drawn out the sword: they have bent their bow. To cast down the poor and needy, to kill the upright of heart. Let their sword enter into their own hearts: and let their bow be broken.” Ps. 33: 22: “The death of the wicked is very evil: and they that hate the just shall be guilty.”

- 36

In certain difficult problems presented by the spiritual life in a concrete case to decide, for example, whether one who at times is in close union with God but is gravely ill, is being inspired by God in certain courses—the outcome of the enquiry will be obscure, but whether the obscurity is from above or from below will depend upon the method pursued.

- 37

One of the councils of the Church says the same with St. Prosper: “That some are saved is the gift of Him who saves; that some perish is the fault of them that perish” (Council of Chiersy, Denzinger, n. 318).

- 38

Cf. Dictionnaire de la Bible, art. Job. The brief summaries given of the long discourses of lob and his friends are taken from Crampon’s translation.

- 39

Cf. the Commentary of St. Thomas on the Book of Job, chaps. 4, 6, 8, 9 (lesson in its entirety), 19, 28. Again St. Thomas, Ia IIae, q. 87, a. 7, 8; De Malo, q. 5, a. 4; and the Commentary on St. John, 9: 2.

- 40

The author has followed Crampon’s translation of the discourses of Job and his friends. The reading of Job 3: 26 is that of the Revised Version. The Douay Version, following the Vulgate, has: “Have I not dissembled? Have I not kept silence? Have I not been quiet?” [Tr.]

- 41

Dictionnaire de la Bible, art. Job, col. 1560

- 42

Le Hir.

- 43

Cf. Dictionnaire de la Bible, art. Job, col. 1574.

- 44

Some of the expressions God uses here to describe the strength with which He has endowed these monsters recall what theology has to say about the nature of the devil. As nature, as reality and goodness, he is still loved by God, for he is still His work. We are reminded, too, that, as St. Thomas says, the devils continue of their nature to love existence as such (as prescinding from their unhappy condition), and life as such; and therefore they continue of their very nature to love the author of their life, Him whom as their judge they hate. Nevertheless, rather than exist in their miserable state they would prefer not to exist at all. (Cf. St. Thomas. Ia. q. 60 a. 5, ad sum.)

- 45

We are reminded of Moses rescued from the waters and the constant assistance given to him by the Lord.

- 46

After the death of the just of the Old Testament, they had to await in limbo the coming of the Redeemer who was to open to them the gates of paradise.

- 47

This is explained by St. Thomas, Ia, q. 22, a. 2: “We must say, however, that all things are subject to divine providence, not only in general, but even in their own individual selves. This is made evident thus. For since every agent acts for an end, the ordering of effects toward that end extends as far as the causality of the first agent extends…. But the causality of God extends to all being, not only as to the constituent principles of species, but also as to the individualizing principles; not only of things incorruptible, but also of things corruptible. Hence all things that exist in whatsoever manner are necessarily directed by God toward some end; as the Apostle says: ‘Those things that are of God are ordained by Him’ (Rom. 13: 1). Since providence is nothing less than the type of the order of things to an end, we must say that all things are subject to it. ‘, St. Thomas also says, Ia, q. 22, a. 3: “God has immediate providence over everything, even the smallest; and whatsoever causes He assigns to certain effects, He gives them the power to produce these effects. As to the execution of this order of providence, God governs things inferior by superior, not on account of any defection in His power, but in order to impart to creatures (especially to those of the higher order), the dignity of causality.” Thus to men has been given dominion over domestic animals which, by their docile obedience, are of assistance to him in his labors. What St. Thomas says in the Ia, q. 22, a. 4, may be summed up as follows: Providence does not destroy human liberty, but has ordained from all eternity that we should act freely. The divine action not only directs us to act, but directs us to act freely; it extends to the very free mode of our acts, which it produces in us and with our co-operation, insomuch as it is more intimately present to us than we are to ourselves. Cf. Ia, q. 19, a. 8.

- 48

That is the mystery St. Paul speaks of in the Epistle to the Romans, 9: 6.

- 49

Cf. St. Thomas, Ia, q. 20, a. 3: “Since God’s love is the cause of goodness in things, no one thing would be better than another, if God did not will a greater good for it than for the other.”